Photo by Maxx Gong on Unsplash Photo by Maxx Gong on Unsplash With longer daylight hours and more time spent outdoors in the warmer air, Summer offers an opportunity to consider the play of sunlight and how it interacts with other natural features. Consider the magical, filtered light of the sun distilled through a canopy of trees. Shafts of light beam down like spotlights, capturing particles moving in the air. The light feels awe-inspiring and effervescent. The Japanese have a word for this: "komorebi". Consider too how sunlight interacts with water. If you find yourself near a body of water--one of New York City’s beaches, like Coney Island/Brighton Beach, the Rockaways, or Orchard Beach, a pond or lake, or even a pool (I am a great fan of NYC’s public pools, like the one at John Jay Park), take note of the light and its dazzling, crystalline clarity. Observe how it reflects off the surface of the water, and how the reflecting changes if the water is still or choppy. Slices of light--patches and dancing light--offer a full-on light show. Notice how the light reflects off the water onto nearby objects--rocks, trees, and other surfaces, offering shimmering reflections of continual movement, with almost cinematic effect, like an experimental film. If immersed in the water, notice how the light filters through the water--a variation of komorebi?--and the shadows on the bottom. Shape-shifting forms moving with the smallest of waves connect the features of light and water. Even raindrops gathered on tree leaves and branches offer a dynamic show as light filters through these tiny translucent reflecting chambers, like small mirrors or lights. Take a moment during these Summer days to notice the light shows around you.

0 Comments

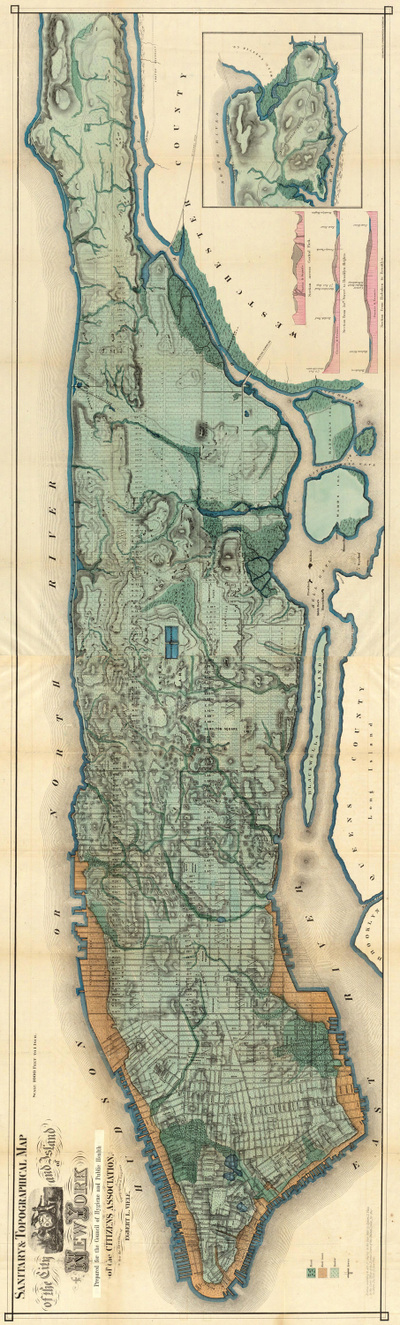

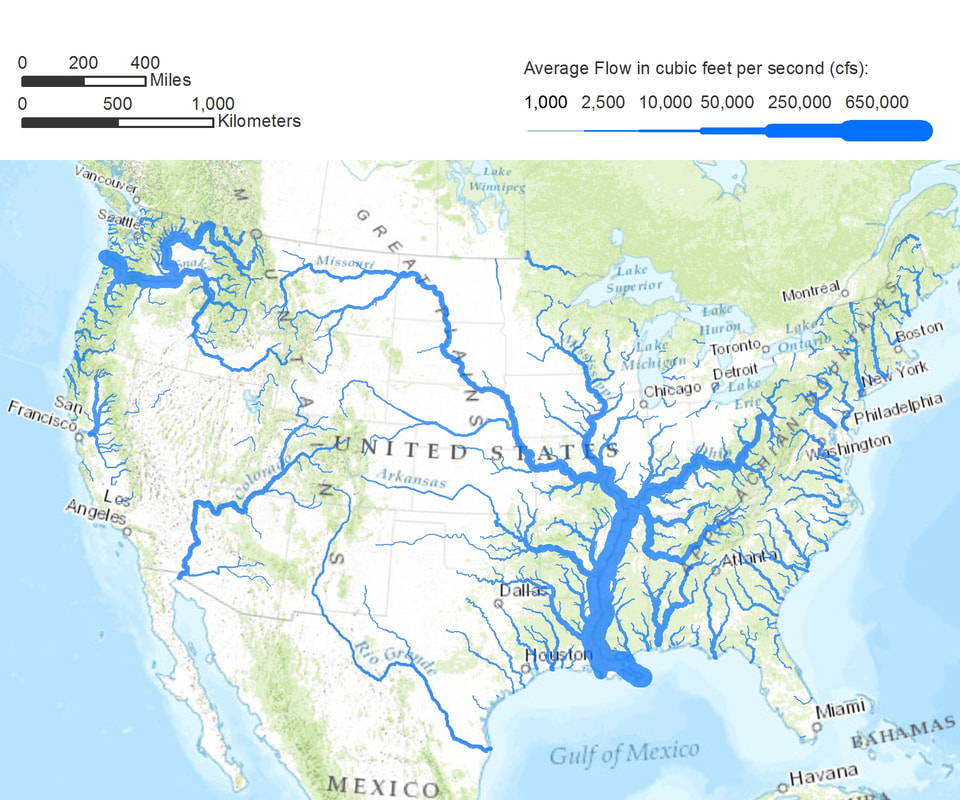

The Central Park Lake The Central Park Lake With a number of days of below-freezing temperatures, ponds in the New York City area are beginning to ice over. Water that just a week ago responded to the subtlest of breezes begins to harden and solidify. The freezing starts on the edges of the pond, where the water is shallow, and crystallizes into a choreography of frozen formations: varying patterns and textures, spindle-like, smooth and pristine, rough and abraded, rivulets and cracks. The ice encases fallen leaves and twigs, a cryogenic embalming that delays their decomposition until the spring thaw. Infinite small bubbles gather below the frozen surface, and peering down through the ice at these glistening spheres seems not unlike gazing through a glass window at the starry night sky. They form a Milky-Way in aqueous suspension. Over the coming weeks, assuming the temperature frequents below freezing, the ice will grow toward the ponds' center, until the entire pond is frozen over. This icy sheath, H20 in its solid state, will separate the liquid world below, the realm of hibernating fish, turtles, and aquatic frogs, from the air above containing water in a gaseous state, including the moisture of our own breath, cloud-like and visible, and comingling with the chilly winter air.  Photo: Jim McDonnell (2018) Photo: Jim McDonnell (2018) Water creates and destroys. It is vital for life, for humans and other animals (we who are mostly water) and for vegetation on which our lives and the lives of almost all other living creatures depend for food and oxygen. It is a source of delight, a tall glass of ice cold water quenching our thirst on a hot day, a cool shower cleansing off the sweat and grit of from a sweltering city day, and a glimpse of a shimmering river, bay or ocean offering a panorama that can fill us with a sense of beauty and awe. Yet, water also annihilates. It turns violent in its machinery of storms, with ravaging hurricanes and wall-of-water tsunamis inundating and destroying homes and possessions and endangering and ending our lives. Over years, water destroys the roofs over our homes. Over eons, it eats away at the land, eroding it to form canyons; as glacial ice, it pushes aside stone, carving grand valleys like giant earth moving equipment. We encounter water-as-destroyer with the arrival of hurricane season, and the 2018 season launched with Florence hitting landfall in the Carolinas this past weekend, swelling rivers, transforming streets into canals, uprooting trees, and destroying homes and lives. Floodwaters continue to rise, with the region’s water supply endangered by contamination from toxic pollutants. Yet, a few hundred miles to the north, with a high pressure system stalling the northward creep of the storm, water was offering its delights to a few dozen swimmers, including myself, participating in an open water event at Coney Island with CIBBOWS, Coney Island Brighton Beach Open Water Swimming, the “Triple Dip”, with options to swim 1, 2, or 3 miles. Despite the devastating conditions in the Carolinas, the conditions at Coney Island were splendid, with air temperature in the mid-seventies and water at a temperature in the low-70s and not unusually turbulent. Swimming at Coney Island offers an experience in contrasts, even separate from markedly different weather systems along the coast. Immersed off the coast in the open water, slicing through modest chop and current, and occasionally bumping into fish, one catches glimpses of the amusement park and its iconic rides: the Cyclone roller coaster, carousel, and Wonder Wheel, looking like giant toys. On the one hand, ocean water, so natural and elemental, and on the other hand, brightly colored attractions built for entertainment. Then again, the water offers its own ride, with wave motion rocking your body and the current redirecting your stroke. But if the amusement park Cyclone was abuzz with activity, so too was a real cyclone, making landfall to the south, and during the day’s swim at Coney Island, the duality of water—like the Hindu god Shiva, destroyer and benefactor—was on many of our minds. After all, it was only 6 years ago that Hurricane Sandy inflicted tens of billions of dollars of devastation in the New York area. Storm surges flooded streets, subways, and tunnels and terminated power for many communities, and we are still experiencing the storm’s effects. The flooded Cortland Street subway station opened just a few weeks ago, and the L train will soon shut down for repairs due to damage incurred from Sandy flooding. Other hurricanes continue to devastate in their aftermath: Maria in Puerto Rico, Harvey in Texas, and Katrina in New Orleans How to reconcile the contrasts in nature? On the one hand, water offered its delights to a group of folks opting for the voluntary adventure of a beach-side open water swim on a sunny day, with a view of a giddy amusement park; yet, a few hundred miles south, water was a force of monstrosity, putting lives at risk. Like the ebb and flow of tides, water gives and takes away. Wind, Water, Stone By Octavio Paz (1979) Translated by Elliot Weinberger Water hollows stone, wind scatters water, stone stops the wind. Water, wind, stone. Wind carves stone, stone's a cup of water, water escapes and is wind. Stone, wind, water. Wind sings in its whirling, water murmurs going by, unmoving stone keeps still. Wind, water, stone. Each is another and no other: crossing and vanishing through their empty names: water, stone, wind.  Egbert L. Viele's "water map" of 1874 Egbert L. Viele's "water map" of 1874 A New Yorker from the 1700s with an eye for watercourses returning today would notice much that is similar to 300 years ago. The Hudson, East, and Harlem rivers still surround Manhattan like a moat surrounding a castle, although landfill has altered the Hudson coastline along the southern tip of Manhattan and the Harlem River was expanded in the 1890s to traverse the tidal straight that separated Manhattan and the Bronx. Newtown Creek still separates what are now Brooklyn and Queens, and the Arthur Kill flows between New Jersey and Staten Island. Flushing and Little Neck bays still border northern Queens, and the Atlantic Ocean borders Brooklyn and Staten Island, leading through the Verrazano narrows to one of the great natural harbors, even if much of the shipping traffic has located to Elizabeth, New Jersey. But for all the still-visible waterways bordering New York City and demarcating its boroughs, much would appear different. Countless swamps, streams, springs, and ponds have been altered. Some still exist, but have been tamed by engineering and relegated subterranean realms, becoming part of New York City's sewer system. Perhaps most notable to our visitor would be the disappearance of the Collect Pond, the source of fresh water for Manhattan’s early European settlers and the Lenape people. What was once a place of drinking water is now a place of law and order. 60 Centre Street, the New York County Courthouse, was constructed over the pond's site, with pumps continually at work to prevent basement flooding. The 2014 redesign of "Collect Pond Park", near the courthouse and featuring a reflecting pool, now highlights this important water resource which was submerged in 1825. Like the Viele map, shown here and completed in 1874, the Nicolls map, completed in 1668 and referenced in John Kieran's 1959 book A Natural History of New York, shows numerous streams traversing Manhattan. As Kieran notes, "the Saw Kill, ran from what is now Park Avenue in the East River at about 75th Street. Montague's Brook ran from what is now 120th Street and Eighth Avenue in a zigzag course to enter into the East River at about 107th Street. It even had an island in it between Lexington and Third Avenues.... Minetta--or Manetta--Brook wandered through the Greenwich Village area...." To put it mildly, watercourse were abundant throughout New York City, and they still are, even if they aren't readily visible. In his terrific website and other writings intrepid urban explorer Steve Duncan identifies hidden watercourse throughout New York City. He notes that Manetta Brook now runs through a 12-foot wide sewer tunnel under Clarkson Street; the spring-fed Collect Pond, described above, in turn fed the marshland over which now sits Canal Street, which in turn became New York's first underground sewer; Sunfish Pond was located between what is now Madison and Lexington Avenues and 31st and 32nd Streets, with Sunfish Creek flowing from the pond to the East River. Tibbetts Brook, which ran near what would become Van Cortland Park in 1899, became what is now the largest sewer line in the Bronx, with the mill pond created when Jacobus Van Cortland dammed the brook in 1699 now a decorative pond in the park. Freshwater resources like Sunswick Creek in Queens and Wallabout Brook in Brooklyn are among the many other waterways that helped make the New York area habitable. Hidden Waters of New York City, by Sergey Kadinsky, also describes New York City's many waterways. Manetta Brook, he writes, is thought to derive from the Algonquin term "manitou or "spirit". Although the brook is now submerged, Minetta Triangle, a small park in Greenwich Village, depicts images of trout along its paths, homage to fish once found in the brook. The location of the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir was once a freshwater wetland from which a branch of the Saw Kill River drained. Signals and indicators of once-visible watercourses remain in place names: Spring Street, Canal Street, Water Street, to name a few. And, though submerged and encased underground, often through marvels of 200-year old brickwork, hidden watercourses routinely challenge urbanization and with it our sense of our own primacy and control over nature. From the early days of New York City's urbanization to present, development plans have been challenged by underground water: Manetta Creek challenging construction in Greenwich Village; the original Waldorf Astoria requiring continual pumping to contain seepage from an underground pond; the renovation of multi-million dollar townhouse on Manhattan's Upper West Side threatened by an underground stream; and according to Duncan buildings near Washington Square Park (2 Fifth Avenue and 33 Washington Square West) once housed fountains displaying water from underground springs. Even in a place as urbanized as New York City, nature courses throughout, submerged underground but still forcefully present, like primal, subconscious thoughts. Skilled engineering may tame and contain New York City's watercourses, but continual effort is needed to control what is ultimately a force bigger than ourselves.  In my previous blog I described the feeling of swimming beneath the George Washington Bridge, the pairing of the mighty Hudson’s natural forces in perpetual ebb and flow and the stately, static grandeur of the human-engineered bridge. And I too was in motion at the nexus of the two, attuned with full sensory capacity to their majesty and interrelationship, witness to a linkage of two interdependent force fields. Few structures embody a human-nature connection more than bridges. To state what is obvious though perhaps often overlooked as we become inured to these fixtures of transportation systems, bridges exist to overcome obstacles imposed by nature. Wherever a bridge exists, so too exists a natural feature that poses a challenge to humankind, whether it be a river, bay, wetland, or valley. “Vaulting the sea”, as Hart Crane said in the poem, To Brooklyn Bridge. Bridges are human-engineered solutions to connect areas whose separateness was eons in the making. They span gaping ravines created by forces of uplift and separation, valleys carved by glaciers, the steady erosive forces of rivers, and bays created by advancing seas. The proportion, elegance, and mathematical symmetry of bridges embody laws of nature, defying gravity and load weight, whether from people, vehicles, or snow. Consider the compression-driven stability of arch bridges, where the weight of and atop the bridge is driven down to the ground, which in turn counters that force, and reinforces the bridge’s strength. So perfect are these structures that 2,000 year old Roman aqueducts still stand. Bridges range from the simplest wooden log across a stream or rope suspension solutions created by the Incas to traverse steep ravines, to the most sophisticated feats of metallic engineering. Bridges can be regarded as a type of magic, erasing impediments created by nature. If medicine makes use of plant-derived potions to cure illness, bridges make use of human-leveraged natural laws of physics to overcome geographic features that separate places. They are transitional spaces, in equal parts a way to and a way from. Employing laws of physics--arches and suspension--and nature’s materials--stone, wood, and metal--bridges at once demarcate and erase the separateness nature has wrought and in so doing offer a hint of the uncanny. Perhaps, then, it’s no wonder that folklore and myth are replete with disturbing creatures inhabiting watery edge-spaces: trolls, both helpers and troublemakers that first appeared in Scandinavian folklore and dwell under bridges or in other peripheral spaces; the fearsome and fanged multi-headed Scylla, transformed from a flirtatious maiden by Circe, and enemy of sailors passing by her in a narrow Mediterranean channel; or the dragon Grendel, describe in Beowulf as dwelling in a swamp at the edge of King Hrothgar’s kingdom. In the case of New York City, bridges span waterways whose origins date back hundreds of millions of years ago, when smaller continents collided into a supercontinent, which then rifted apart, creating a continental margin at what is now the Hudson Valley. Subsequent collisions, the absorption of a volcanic island arc, and the relatively recent (concluding 10,000 years ago) scouring of the land by glaciers carved the Hudson Valley further and left behind a moraine that shaped and created New York City’s bays and inlets, and even the Long Island Sound, flowing into the East and Harlem Rivers. Bridges not only span the remnants of millions of years of geologic activity; they occasionally take advantage of them. The George Washington Bridge was built in its location, with the steep Palisades on the west side of the river and Washington Heights on the East side, in part to take advantage of the cliffs left in place by ancient geologic activity, which eliminated the need for lengthy approach ramps to avoid interfering with maritime traffic. Spanning Newtown Creek, the Gowanus Canal, and the Hutchinson River; connecting City Island and Rockaway; and connecting Queens to the Bronx, Brooklyn to Staten Island and Staten Island to New Jersey, there are over 60 bridges in New York City. They range from arch bridges, to suspension bridges, to draw bridges, to one of four "retractable" bridges in the country. Manhattan is linked to neighboring boroughs and New Jersey by 20 bridges, the oldest of which, the High Bridge, which crosses the Harlem River and links the Bronx and upper Manhattan, was initiated by the need to transport water from upstate resources to the growing metropolis of Manhattan. Constructed in in 1848 as a stone arch bridge, the High Bridge looks like a Roman aqueduct. It took 35 years for the next bridge to be completed, the Brooklyn Bridge, a marvel of engineering that reinvented suspension bridge engineering by bundling multiple strands of steel cable, considerably enhancing the strength and load-bearing capacity of the bridge. From simple to grand, crossing small creeks and powerful rivers, New York City’s bridges not only connect distinct locations. They also tell a story about the natural geography they inhabit.  Sanya circumnavigation crew member Catherine North at North Cove Marina Sanya circumnavigation crew member Catherine North at North Cove Marina New York City is surrounded by wilderness--REAL wilderness, not the "urban jungle" or cut-throat work culture of high finance on Wall Street. The waters that surround New York and connect it to far away places offer a vast, undeveloped environment beyond the control of humankind. And what better way to experience this expanse than by sail boat? Docked until June 25 at the North Cove Marina in Battery Park City, and at other times this week at Liberty Landing Marina across the Hudson in Jersey City, are a dozen 70-foot racing yachts preparing to embark on the eighth and final leg--the 2,000 miles from New York to Derry-Londonderry--of a year-long race around the world. The Clipper Race is a 40,000 nautical mile race created by Sir Robin Knox-Johnson, the first person to sail solo non-stop around the world. Knox-Johnson recognized that more people have climbed Mount Everest than sailed around the world and was motivated to change this. With the aim of opening adventure sailing to a wider audience, the race invites everyday people to participate and is now in its eleventh season. A friend, Catherine North, is crew member for Sanya Serenity one of the twelve boats in the race. While some crew members participate in only one of the eight legs, Catherine is on board for the full ride. I was fortunate to be able to spend some time with her during her stopover in New York and to learn more about her breathtaking adventure, an adventure she describes as teaching her even more about herself than it has taught her about sailing. The race started last July in Liverpool, with with stopovers in Uruguay, South Africa, Australia, China, Seattle, and--now--New York. And along the way, the fleet made two Equator crossings, traveled along the Tradewinds, through the Doldrums, across the Atlantic and the South Atlantic, around the Cape of Good Hope, amid 80-foot swells and 70 mile-per-hour winds, through the South and East China Seas, across the International Date Line, across the Pacific, through the Panama Canal and the Caribbean, and on to New York, before heading along the Gulf Stream and Labrador Current on the final leg across the Atlantic. If you have a chance, check out the Clipper Race fleet in our nearby harbor (open tours are available until the 23rd). And even if you aren't able to see the fleet, invite your imagination to carry you across the city's nearby water, out through the harbor and on towards distant lands. Who looks upon a river in a meditative hour, and is not reminded of the flux of all things? — Emerson, Nature The Mohicans called it Muhheakunnuk, “the river that flows two ways", recognizing the Hudson as not only a river but a tidal estuary, where south-flowing fresh water collides with saline sea water pushing north twice a day, like a giant, slow-motion exhale. With a recent post focusing on waterways and cities, let’s take a moment to appreciate the magnificent river flanking New York City’s west side, a river that attracted native inhabitants; beckoned explorers, from Verrazano to Hudson (in search of a waterway to China); helped a new nation grow and achieve global influence; inspired a school of art influenced by Romanticism; and even has a museum dedicated to it (in Yonkers). Its headwaters in the Adirondacks at an altitude of over 4,300 feet, the Hudson begins as a series of alpine brooks and ponds – Lake Tear of the Clouds, to Feldspar Brook, to Opalescent River, and then Calamity Pass Brook and Indian Pass Brook to Henderson Lake, where a convergence of rivers become “The Hudson”. Winding its way south to Troy, the northern reach of tidal influence, it widens and continues on its 315 mile route. Reaching its widest point of 3 ½ miles in Haverstraw, it continues past Manhattan, and flows beneath the Verrazano Bridge, through the Narrows between Brooklyn and Staten Island and into the Atlantic Ocean. But it doesn’t end there. At the mouth of the Hudson River begins the Hudson Canyon, a submarine canyon extending over 400 miles into the Atlantic, cutting through shallower continental shelf and then dramatically into the deeper ocean basin. With walls reaching ¾ mile from the ocean floor at its deepest point, 100 miles off shore, it rivals the depth of the Grand Canyon’s mile-deep cliffs and is one of the largest submarine canyons in the world. Last exposed over 10,000 years ago, during the last ice age, the canyon formed when the sea level was 400 feet lower and the mouth of the Hudson was 100 miles east of its current site. If you can, take a look at the river. You might notice it flowing north! You also may notice a patchwork of movement across its surface – central sections dredged deeper for shipping perhaps moving more swiftly than shallower areas along Manhattan and New Jersey, various micro-currents, and the influence of wind. Think about the clash of forces and wave patterns when the tide is moving in, pushing against the current. And think about how quickly the river moves when the tide is outbound, a double whammy of south-bound current and outbound tide conspiring. Think about traces of the Hudson continuing off shore, through one of the world's deepest submarine canyons, and about the ebb and flow of the river that flows two ways. Suddenly Poughkeepsie Grace Paley, 2007 what a hard time the Hudson River has had trying to get to the sea it seemed easy enough to rise out of Tear of the Cloud and tumble and run in little skips and jumps draining a swamp here and there acquiring streams and other smaller rivers with similar longings for the wide imagined water suddenly there’s Poughkeepsie except for its spelling an ordinary town but the great heaving ocean sixty miles away is determined to reach that town every day and twice a day in fact drowning the Hudson River in salt and mud it is the moon’s tidal power over all the waters of this earth at war with gravity the Hudson perseveres moving down down dignified slower look it has become our Lordly Hudson hardly flowing and we are now in a poem by the poet Paul Goodman be quiet heart home home then the sea  On the heels of the previous blog, Overview, take a look at a map of where you live, preferably in satellite view. If you are like most people, you live in a densely populated area. But why is your home region located where it is? Take a closer look, and you will notice a nearby river, lake, or ocean, or combination of these, not only providing access to drinkable water but also enabling the transport of goods long before the availability of railroads, when the only alternative was costly overland transport via wagon and pack animal. New York City sits at the nexus of the Hudson River and the Atlantic Ocean, and its location near major waterways is key to its prominence on the world stage. In Gotham, Edwin Burrows and Mike Wallace describe some of the geographic features of New York that led New York to become "the principal link between the United States and world markets." Its location on the Atlantic, with a deep harbor accessible to the open ocean and rarely impeded by ice, led to regional and global commerce, with markets in the West Indies and Europe for farm products and cotton. By contrast, Boston's Harbor was often blocked by ice in the winter, and Philadelphia, 100 miles from the mouth of Delaware Bay, was accessible to large vessels only during flood tide. But it was the Hudson that connected New York City to the interior of the content and led to the development of a nation. Canals constructed in the 1790s linked the Hudson with Lake Champlain and Lake Ontario, extending the the reach of New York City into hinterlands along Lake Erie and western Pennsylvania. Completed in 1825, and later enlarged, the Erie Canal—America’s first super highway—contributed to New York City’s global ascendancy by creating an inland navigable waterway connecting the Great Lakes to the Atlantic and enabling the transport of inland mining and agricultural goods to overseas markets. This engineering feat was made possible by the geologic good fortune of New York State: an east-west gap in the Appalachian Mountain chain, along the Mohawk River valley between the Adirondack and Catskill Mountains. Extending over 1,500 miles, 400 miles inland from the Atlantic Coast, the Appalachians were a considerable barrier to western migration and trade, with only five east-west gaps allowing travel by pack animal. Notice other cities central to manufacturing: Duluth, Minnesota, on the western edge of Lake Superior, in the heartland of North America, 1,500 miles from the Atlantic coast in a region rich in iron ore and accessible to the beaver fur trade; Chicago and Milwaukee, abutting Lake Michigan; Detroit on Lake Erie, via the Detroit River; Cleveland and Toledo on Lake Erie too. These interior cities are port cities because of their access to the Atlantic, first via the Erie Canal and later via the Great Lakes Saint Lawrence Seaway, more recently named "Hwy H2O". Consider Minneapolis, with access to the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River; Saint Louis, at the juncture of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, the gateway to the west, with the Missouri extending to its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains in Montana; and New Orleans, on the Gulf of Mexico at the Mississippi estuary. And take note of countless cities and towns along major rivers of the U.S.: the Connecticut and Housatonic, Mohawk, Delaware and Schuylkill, Monongahela, Susquehanna, Allegheny, Ohio, Platte, Arkansas, Tennessee, Savannah, and Potomac, supporting the manufacturing of textiles, lumber and paper mills, and steel and transport of goods. The same waterways that enabled industry and transport, which in turn gave rise to cities and towns, attracted our country’s original inhabitants; what is now Manhattan, Philadelphia, Washington DC, Detroit was once occupied by other nations--Manhattoes, Lenape, Erie, Illinois, Pequot, Mahican, Ojibwa, Delaware, Powhatan, Huron, and Cherokee, to name a few. Contemporary place-names, rolling off our tongues with such familiarity that we rarely think about their original references, are reminders of the legacy of these earliest inhabitants. And of course, proximity to water isn’t unique to US cities. Paris’s began on an island in the Seine; London on the Thames; Istanbul on the Bosphorus; Agra and New Delhi on the Yumana. And grade school children learn of the “cradle of civilization” developing between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. These days, with water magically appearing out of our kitchen and bathroom faucets and goods available to us in stores and via online delivery, it's easy to disregard the impact of nearby waterways and their significance in the location of our major towns and cities. But, towns and cities are located where they are because of the availability of resources and transportation, with oceans, rivers, and lakes functioning like giant vascular systems enabling access to resources and materials and the exchange of goods, long before the invention of the railroad and air travel. Take a moment and consider your nearby waterways, and how they helped shape the place where you live.  Photo by Nancy Kopans Photo by Nancy Kopans The rain was falling lightly during my walk to work today. It cast a sheen on built surfaces, transforming sidewalks and streets from gritty and dull, light-absorbing flatness to illuminating mirrors. Puddling in the depressed edges of sidewalk squares and in random fissures and crannies, it highlighted the imperfections in the controlled straight-line geometry of our built environment. Rivulets of small steams ran curbside, the water braiding in patterns as it found its way down micro gradients that barely were perceptible when the surface was dry. Gently, the drops hit the ground with a light, feathery drumbeat. Falling on puddles, each drop created rings of concentric circles, with small waves expanding outward and intersecting neighboring circles in a dance of geometry as wondrous and revealing as my childhood Spirograph toy. Drops gathered at the tips of tree branches like little crystals reflecting light. As we know, each drop fell from the sky, part of "the water cycle" we learned about as children, a cycle that connects land, sky, and ocean and stretches back hundreds of million of years. Walking along the city canyon of buildings, my line of vision is limited. But I think about what this weather system looks like from overhead or at a distance. I think about how in wide open vistas one can observe the rain from afar looking like a dark column connecting deeper gray clouds in the sky and earth. Some Native American tribes have referred to these columns as tall women moving across the Plains. Rainfall in a field or forest is delightful, with water enhancing deep greenery and dripping off leaves. But rain in a city reminds us that nature and its cycles are always with us. It transforms urban micro plains and surfaces, enriching their colors and calling out asymmetries and forces of gravity and nature that even the most focused efforts of humankind to tame cannot overcome. Consider taking a walk on a rainy day. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed