The COVID-19 crisis highlights many things about our ways of being: our woeful lack of preparedness for a pandemic; the broader need for health care; the power of a force of nature so much greater than ourselves and our political structures and leanings; and the impact of job, housing and wage disparities among populations, among them. It also, and perhaps most strikingly, underscores our interconnectedness. Indeed, central to the coronavirus' spread are the complex webs of links among beings. The virus jumped species, moving from non-human creatures to people, and once rooted within people, each point of human contact becomes its own node of countless connections, and on and on. It's our nature to be social creatures. We engage with family, friends, work colleagues, and fellow travelers on boats, airplanes, buses, and trains. We engage with fellow shoppers, theater-goers, congregations, book club and sports and exercise pals. We hug, we embrace, we walk hand-in-hand. With the virus persisting on surfaces and in droplets of moisture in the air, our awareness of even traces of human connection become amplified. If I touch a door knob that was touched by someone with the virus who coughed into their hand, and I then rub my eyes, what then? If I handle groceries touched by someone with the illness and then scratch my nose, will I become infected and infect my family? If I walk along a path where an infected person recently sneezed and I inhale that same air, will I succumb to the virus? We become attuned to the invisible strands of countless connections as if we are wearing special lenses or possess a superhero-like powers akin to a UV light that discerns not just actual human encounters but residues of encounters, including those that are intermediated by the surfaces we touch and the air we breathe. So much of what it means to be human--so much of how we define ourselves--is in relation to others and the roles we play as members of multiple communities. Part of what makes combating the virus' spread is the need to isolate. This runs against our nature, how we identify ourselves, and our deep need to connect with others. Most glaring in the midst of this crisis are the daily tragedies: countless heart-wrenching experiences of illness and death, loss of jobs, disrupted schooling, and unprotected health care workers. Another, albeit minor, awareness is how interconnected -- and interdependent -- we all are. We are witnessing how a virus originating in central China has, by virtue of the extent to which humans travel and connect with one another, reached people all over the world. Yet, what is alarming in the context of a virus that causes illness and death and other hardship, is also an indicator of our human interconnectedness. May we one day be able to appreciate that interconnectedness in a context separate from the horrors of a pandemic.

0 Comments

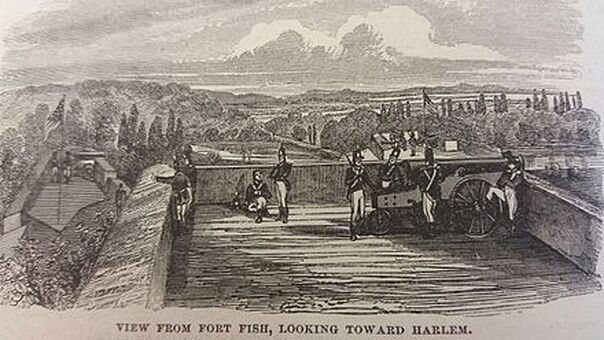

My "shadowflection" in Forest Park, Queens My "shadowflection" in Forest Park, Queens Shadows evidence physical presence--the instantiation of our bodies and of other creatures and structures. Bathed in daylight, our corporeal forms have the power to block the Sun's rays and cast dark reflections on the ground, what David Abram calls our "shadowflection". Even nighttime, as Abram notes, is nothing other than a hemisphere of the Earth enveloped in its own shadow. So too, shadows remind us of the sun's presence, and our position relative to it as we stand upon the Earth, our orbital home in continual motion. As the Sun migrates from low on the eastern horizon in the morning, to overhead, to low on the western horizon in the evening, our shadowflections shapeshift by the hour and season. Transitioning from elongated versions of ourselves, as if we were giants standing on the earth, to squat, to long again, they remind us of the continual motion of the Earth relative to the Sun, and perhaps other cycles and changes our bodies experience over the cycles of days, months, and years. And far more than a two-dimensional surface-restricted image, shadows have three-dimensional depth. Writes Abram in Becoming Animal: "My actual shadow is...more substantial than that flat shape on the paved ground. That silhouette is only my shadow's outermost surface. The actual shadow does not reside primarily on the paved ground; it is a voluminous being of thickness and depth, a mostly unseen presence that dwells in the air between my body and that ground. With the summer sun high in the sky, it is prime time for shadowflections, reminders of the our ever-present connection with the Sun, as the Earth turns and turns.  While we celebrate July 4th--Independence Day--with fireworks and barbecues, America's Revolutionary War still can seem like an event in the distant past. After all, 1776 was 243 years ago. Yet, traces of the war are apparent, vestiges written into, if not shaped by, the topography of the landscape itself--even in New York City. Central Park's steep bluffs overlooking the Harlem Meer were important strategic features during the American Revolution, their elevation and expansive views providing the site for the military fortifications Fort Fish, Fort Clinton, and Nutter's Battery, sites still on view today. During America's War of Independence, George Washington defended New York against invading British forces from this high-ground position that is now the northeast section of Central Park. The British defeated Washington in the area and built a series of fortification extending from the bluffs to the Hudson. In addition to Fort Fish, Fort Clinton, and Nutter's Battery, the British constructed a chain of blockhouses, the site of one of which is in Central Park's Northwoods, adjacent to 109th Street. Each of these locations was subsequently used by Americans to defend against the threat of British invasion from the north during the war of 1812. McGowan's Pass was another key topographic feature during the Revolutionary War in what is now Central Park. Located along the steep hill and switchbacks of what is now the park's East Drive north of 102nd street, it was a Hessian (conscripted German soldiers) encampment for much of the war, from 1776 to 1883. At the war's end, the Hessians and British retreated north through pass, while George Washington reentered New York through the pass. Gazing at today's runners and cyclists traversing topographies of Central Park that during the Revolutionary War were strategic locations suggests more than weekend warriors. One can, with a little imagination, time travel and conjure warriors of the American Revolution traversing the same terrain and making use of its features. Landscapes carry memory.  Heightened attention to early flower blooms, described in my previous blog, has awakened my visual awareness and made me more attuned to forms and structures everywhere. Lately I've been particularly attuned to surfaces. By "surfaces" I mean the outermost layer, perceived by sight and touch--boundaries and edges that define, separate, and connect. Consider the many ways to describe surfaces, the characteristics that define them, to name a few: smooth, rough, patterned, textured, hard, soft, straight, curved, color, symmetrical, matte, shiny, reflective. And often, surfaces become all the more intricate the closer one looks. What appears as smooth may in fact be comprised of grooves and particles, with infinite complexity. City life offers an opportunity to notice the surfaces of our built environment, the geometric, smooth facades of buildings, sidewalks, stairways, and interior spaces--walls, floors, ceilings, furniture. What a contrast these views are to the undulating, uneven and surprising surfaces of the natural environment, of trees, flowers and shrubs growing along streets and in parks, of rocks and water. Some say that the "Euclidean geometry" of our built environment impairs our "visual fluency", that we innately crave the visual complexity offered by natural environments, visual fields that feed our brains' ability to absorb complexity. Yet, it is worth considering that the materials that create our built environment derive from natural materials: wood harvested, stones gathered and cut, and metals mined and smelted, transformed from their natural state to be put to our use. On a micro-level, their true natural forms become apparent: the cellular structure of wood, and crystalline structure of metals and rocks. What began as an ordinary day transformed into sensory adventure as I tuned into the surfaces around me.  Photo by Nancy Kopans Photo by Nancy Kopans Nature is ever at work building and pulling down,… keeping everything whirling and flowing, allowing no rest but in rhythmical motion, chasing everything in endless song out of one beautiful form into another. – John Muir During a recent forest bathing walk a participant wondered whether “motion = life”. I have pondered this observation, thinking about how not everything alive is in obvious motion. Yet, on closer examination there is motion – a heartbeat, cellular activity, the vascular activity of plants. Perhaps it is this sense of “motion = life” that leads people to comment on how alive the city is, how it has energy, with its buzz of activity – people walking, taxis zooming, neon signs blinking -- like a giant organism. There are few better ways to experience a city and its whirl of motion than on a bicycle. On a bike one moves fast enough to get somewhere, but slow enough to see what’s around. And beyond seeing, there’s what’s experienced. There’s no glass or metal to separate us from surroundings, and with speed quickened from the pace of walking, senses become alert -- the sight of pedestrians stepping into a nearing intersection with the changing of a light, the feel of the breeze (even on a hot, muggy summer day), the sound of a siren somewhere. Streets become like a river, the bike like a kayak navigating white water. Being in motion, the turning of wheels propelled by the force of pedaling, seems to conjure the motion all around while making oneself a part of that motion too. There’s a sense of keeping time, the rhythmic motion of wheels spinning round, the rhythm of people walking, of cars moving, stopping at red lights, moving at green, creating a choreographed dance of people going places, everyone at their own rhythm, but collectively like a grand percussion symphony. The compactness of the city becomes apparent. Neighborhoods awkward to connect on a grid, such as a trip diagonally across town, or identified as geographically distinct zones (Uptown, Midtown, Downtown, East Side, West Side) can be traversed or connected within minutes, while allowing the rider to see all that is in between, stitching together the entire pattern of the city rather than starting at Point A and popping up at Point B, as in the case of a subway, with no clue of what’s in between. With this comes a feeling of independence, of being liberated from the constraints of the contained pods of subways and cars, with the vicissitudes of their interior space, and the slower pace of walking, even at the speed of a New Yorker still slower than on a bike, If distances are felt, so too are the city’s gradients. The paved-over hills and valleys that we are blind to when in a car, bus, or subway become apparent and experienced – a felt reading of the terrain. Biking puts the “hill” back in Murray Hill, Lenox Hill, and Carnegie Hill. And even in 94 degree soupy muggy weather, there’s a breeze. But if there’s freedom on a bike, there’s also a connection to civilization, and in this way biking in the city seems like a pure expression of what it is to be alive and human in a city. A bike after all is forged from metal, pure Vulcan (albeit from earth-sourced element) technology, and pairs beautifully with pavement for a smooth, human-propelled ride, a blending of the natural, ever-moving creatures that we are and technology. Although I’ve done a lot of road riding, including a self-guided cross country trip with a pal and a NYC-New Orleans self-guided trip with another pal, much of my riding these days is via Citibike, New York City’s bike share service. Citibikes are hearty 3-speeders with upright handlebars. They remind me of my childhood bike, with its banana shaped seat, handlebar basket, and plastic streamers radiating from the handlebar tips (how they moved in the wind!). What joy in that memory, awakened when I’m on a Citibike. My own Rosebud. I commute to—and when the daylight is long—from work by Citibike a few days a week. According to my Citibike app dashboard, I’ve gone on 605 rides, lasting collectively 266 hours (time much better spent than in a subway or taxi!), with aggregate mileage thus far of 1,988. That’s just about the distance from New York City to Cheyenne, Wyoming. There are days when I like to imagine that I’m on a stretch of road along that route. On a bicycle, imagination is free to roam. Recent posts--Overview and HwyH2O--tuned into the perspective of looking down from above. Now let's shift our perspective 180 degrees and look up. After a warm spring Saturday spent mostly in Central Park, I returned home for dinner with the intention of returning to the park to enjoy twilight. But, by the time dinner was over I had lost my motivation. With my teenage daughter absorbed in end-of-semester exam prep and paper writing, I felt like being nearby. Had we a porch or patio, I would have delighted in stepping out onto it to enjoy the warm spring evening while my daughter continued with her homework indoors. One of the challenges of living in a city like New York is that it's not so easy to step outside from our homes. We apartment dwellers can't just open a door and walk onto a patio, lawn, field, or forest. Going outside is a production, requiring walking down flights of stairs, or a ride in an elevator. A favorite anecdote highlights this difference. I was in the country with my girls, at a house with a sliding door leading to an outside deck. My older daughter, who must have been about five at the time, pulled the door open and stepped outside, shut the door, then pulled it open again and stepped back inside, and repeated this several times, all the while saying, "Inside. Outside. Inside. Outside." A city kid, she was marveling at the realization that she so easily could transition from indoors and outdoors, a transition that is far more complex in her city home. When the days are getting longer and the air is warmer, I miss the ability to just step outside. I begin to feel a bit out of sorts, claustrophobic perhaps, as if entombed, and think about growing up in a leafy New York suburb. As I kid on an evening like this I likely would be playing kickball with the neighboring kids until our mothers called out for us to come home for dinner. We'd quickly chow down our meals and run back outside to continue the game until near darkness. No longer motivated to walk the few blocks to the park, I decided to head to the roof of my building, a flight of stairs up from my apartment. The building's roof is unfinished, and the view would not be considered exceptional. There's no direct view of the sunrise or sunset, no view of water or a park. A small, low-slung building, we are surrounded by larger buildings blocking any possibility of seeing the horizon. But the view upward is not blocked. My initial intent was to read, and although the book I'm reading is engaging, a voice inside me kept saying, "notice where you are." I put the book down, reclined in my on-the-ground adjustable hiking seat, and began to notice the sky. Layers of clouds moved across the great blue expanse, with clouds higher up illuminated by the setting sun, giving them yellow-pink tinge. Grayer clouds below portended predicted rain. And all the while, in a faint rhythm of surges and releases, a warm breeze enveloped me and let go, the same wind that was making the clouds move, the same wind that was making the branches of trees wave in a penthouse garden across the street. Every few minutes a plane crossed the sky, people in motion within a sky in motion. A helicopter buzzed across at a distance, like a mechanical firefly. As the daylight dimmed, lights in apartments begin to flick on. I stood up to wander about and from a new viewpoint, no longer blocked by a neighboring building, could see the moon in the south east sky, a halo surrounding its glow. Ever in a cycle of change, it was now a waxing gibbous, but in a few days would be a full moon, May's "Full Flower Moon". The world around me was in a cycle of motion and change. For over an hour, I looked upward from the unadorned rooftop, enchanted by the movement above and around me, seeing it with my eyes, feeling the warm wind touch my skin. The nearby buildings seemed small. The sky felt infinite.  A recent blog focused on the Atlantic Flyway and the great spring migration of birds from tropical regions to northern breeding grounds. It's thrilling to witness the many species of birds that pause in our urban parks to rest and refuel. Thinking about birds' great aerial passage is also an opportunity to consider for a moment a birds' eye view. Places--many familiar to us when we are dwelling or moving within them--can look vastly different from overhead. Patterns emerge and one can't help develop an awareness of the interconnections among localities and regions across the earth. Artist Ben Grant explores this perspective in his book Overview. What began as an Instagram project is now a book with more than 200 breathtaking, high definition satellite photographs of industry, agriculture, architecture, and nature highlighting uncanny patterns and the impact of human existence. Says Grant, “From a distant vantage point, one has the chance to appreciate our home as a whole, to reflect on its beauty and its fragility all at once." Grant's book is well worth perusing and exploring. His work not only offers perspective on interconnections across landscapes and the human impact on our planet; it can inspire us to be aware of what an overview perspective might offer us in our current location--how our familiar surrounding buildings, blocks, avenues, and parks look from above. We can take time to imagine this perspective, and we also can explore the perspective Google Maps satellite view offers as a way to notice our environments from overhead. Beyond viewing location from above, we can consider the overviews available to us on a smaller scale, from our own, human vantage points--the forms and patterns observable to us at ground level as we move about or just pause to take it in. I think about a lovely New England lake where I enjoy swimming during the summer. How thick and robust its underwater vegetation becomes by mid-summer, with tendrils billowing in the murky water in a spectrum of shades of green, from deep olive to sweet pea. Skimming the surface stroke after stroke while gazing down through my goggles, I lose my sense of scale and imagine myself to be in flight, soaring through the air while peering down on a vast mass of flora below, a primeval jungle or forest.  There has been much discussion lately about colonizing Mars. SpaceX owner Elon Musk expects to initiate Mars spacecraft test flights as early next year and plans to land cargo spaceships on the Red Planet in 2022, with a manned landing targeted for 2024. Mars One aims for a permanent manned landing in 2032. One has to be in awe of the vision, science, and courage it takes to plan and participate in these initiatives. Perhaps the desire to settle Mars is motivated by core characteristics of human nature, our innate curiosity impelling us to voyage ever onward to faraway reaches. From the time hunter gatherers traversed ice bridges across the Bering Strait and vast bodies of water on wood-carved canoes, humans have used their ingenuity to venture forth to distance lands. Even our origin stories, from the Navajo creation myth Upward Movement and Emergence Way to Old Testament desert wanderings in search of the promised land describe similar outward migrations. Perhaps colonizing Mars is the latest chapter in this narrative. Yet, some of what is motivating consideration of Mars colonization appears to be an evolving sense of dissatisfaction with the condition of our planet, a sense of unease about political and resource stability and with this concern about the future survival of humankind. Two hundred years ago there were less than 1 billion people on our planet. Today there are more than 7 billion, with the population expected to exceed 10 billion in another 30 years. Population growth combined with the impact of climate change and resource depletion have prompted concerns about a dystopian future in which human life on Earth is at risk. Perhaps this is not dissimilar to what motivated our ancestors to migrate as well. But the fact is that we have a pretty great planet right here. Colonization of Mars or other potentially habitable reaches of our galaxy requires addressing complex challenges regarding gravitational differences, oxygen and water production, food production, energy production and storage, building habitats, and countless other challenges. While human ingenuity could surmount these challenges let's be clear: Earth, our home, offers plentiful water, oxygen, and natural resources for food, clothing, and shelter, as well as for transportation, energy, and medicine, and if well-tended by us can support us for future generations. At the same time that we look to colonize Mars, how can we tend to our current home in a way that recognizes how much we are part of it and dependent on it, and in a way that secures it for future generations? Our ancestors understood this, even if they too responded to yearnings to explore faraway reaches. Long ago, people lived in close relation to the Earth, highly attuned to this symbiosis. They understood that being human means being part of the natural world, having a sense of belonging and recognizing that the Earth nurtures. As Robert Wolff writes in Original Wisdom: Stories of an Ancient Way of Knowing, [Aboriginals] lived off the land or the ocean. They did not have to rely on the outside for any of their needs. They could find all the food they needed to sustain themselves, they could find or make material for shelter and clothing. They carved canoes and made blowpipes, they rolled a powerfully strong rope from the fibers of coconut husks. And beyond what they could find and make in their environment, they did not need anything, nor did they want anything more. They lived life. Life did not live them, as it does us. Most of us have ventured far from this way of life. We no longer live in tightly bound communities. We no longer live directly off the land, nor do we eschew material possessions, regarded by nomadic people as a burden to carry. Yet the truth remains that everything around us, ourselves included, derives from the Earth. We are nearly 70% water, and beyond that a combination of elements with a magical spark of life. Our food, our clothing, our shelter all derive from earth. The concrete underfoot in our cities, the metal comprising our cars, the elements that comprise the computer I am writing on and you are reading on, our sources of energy--all derive from the earth and the systems in which it exists. On this Earth Day, take a moment to think about the threads that connect us to our ancient lineage, to ways of life closely tied to the Earth and its resources, and think about how the core of that lineage has not changed. While perhaps one day humankind will colonize Mars, appreciate the wonder and beauty of planet Earth and the many ways it nurtures us.  From ants to elephants, from grains of sand to mountains, life and matter present in a spectrum of sizes, each bearing complexity. Each grain of sand contains micro peaks and valleys, variations in form from angular to rounded, and complex mineral composition, including varying combinations and proportions of quartz, feldspar, pyroxene, gypsum, amphibole, garnet, epidote and other minerals. Though on a smaller scale, a grain of sand can reveal the complexity of an entire mountain, much like how to an ant a field of grass is a forest. As the poet Gary Snyder writes: As the crickets’ soft autumn hum is to us so are we to the trees as are they to the rocks and the hills The iconic 1977 science film "Powers of Ten" explores the relative size of things in the universe and the impact of adding or subtracting another zero to their scale. Beginning one meter above a man and woman on a picnic blanket in a park on the Chicago lake front, the film extends out from the park at incremental increasing "powers of ten": 10 meters, 100 meters, 1,000 meters and so on exponentially, one order of magnitude every ten seconds, until it reaches 10 to the 24th, the outer edge of the known universe. The film then reverses course, zooming back to the picnic blanket at decreasing orders of magnitude. From there, it zooms into the man’s hand at negative powers of ten until it reaches 10 to the -16th and subatomic particles. Conveying the universe as “an arena of both continuity and change, of everyday picnics and cosmic mystery” (as stated on the website of Charles and Ray Eames, the film’s creators), the film is one of my favorites. It reminds us that there are “worlds within worlds” and that with sensitivity to scale and perspective we can embrace these varying dimensions and the sense of wonder that comes with exploring them. I invite you to take a look at the film, below, and think about what it can teach you about exploring the world on different scales.  Dressed in his wolf suit and wreaking havoc in his home, Max is sent to his room without any supper. Magically, his room transforms into a forest. Max sails to the land of the Wild Things, who eventually coronate him as their king, with a wild rumpus to celebrate. In time, Max tires of the land of the Wild Thing and sails back home. He returns to his room, where soup his mother has left for him is still hot. Alice tires of sitting by her sister Lydia along a riverbank and listening to her read a book without pictures when she notices a white rabbit scurrying by. Following after him down a hole she encounters a hookah-smoking caterpillar, the Cheshire Cat, the Queen of Hearts, Mad Hatter and others. On the verge of being beheaded, she finds herself back at the riverbank with Lydia. And in The Lion, the Witch, and The Wardrobe, the Pevensie children--Lucy, Edmund, Susan and Peter--enter the magical world of Narnia through what appear to be an ordinary piece of furniture. There they encounter Aslan the lion King, the White Witch, and others and grow into adulthood, only to one day tumble through the wardrobe back into the "normal" world and learn that no time has passed. Where the Wild Things Are, Alice in Wonderland, and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, remind us of the ability of imagination to expand time and experience. In what turns out to be very little little time at all, Max, Alice, and the Pevensie children encountered elaborate adventures, experience courage and fear, and grow--and, in the case of Alice, shrink too. Were all of these characters only dreaming? Children would question that assumption; they know that with a little imagination adventure can be found at almost any moment, and imaginary encounters can feel just as authentic, if not more so, than "normal" life. Can we as adults, in the context of our daily lives and our many responsibilities, and without relying on technological distractions, find moments to venture to where the wild things are, including our own inner wildness? How can we find the rabbit holes or wardrobes that enable us to discover liminal worlds that offer not only a break from the ordinary but also a chance to get in touch with aspects of ourselves, and perhaps more authentic aspects, that don't get a lot of attention? For Max, noticing trees growing in his room led him on his adventure. For Alice, it was a white rabbit in a hurry. And for the Pevensie children it was sensing the crisp cold of snow. While we may be many years from childhood, we too can use our senses and imagination to augment and enrich our daily lives, to discover "pocket adventures", and we can do it by noticing nature. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed