|

One of the joys of guiding Forest Bathing walks is meeting people who feel a deep connection to parks and trees. It is in this capacity that I met Rita and John, who invited me to guide in East River Park this coming weekend and who, along with their community, are passionate stewards of East River Park and its trees. History Located on Manhattan's Lower East Side, East River Park is a beloved public green space that was established in the early 1900s as a way to provide a recreational area for the growing population of immigrants in the area. In the 1930s, the park underwent a major expansion, thanks in part to the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal program that provided employment opportunities for thousands of Americans during the Great Depression. The WPA oversaw the construction of new playgrounds, sports fields, and other amenities, as well as the planting of thousands of trees and shrubs. It is many of these very same trees that recently have been cut down in connection with a redevelopment initiative. Some are still standing - 80+ year old oaks and plain trees - but too are to be cut down. They are marked with numbered, coin-like metal tags, like dog tags worn by soldiers going into battle, carrying an indicator of doom. Over the years, the park has continued to evolve and adapt to the changing needs of the community. In the 1960s and 70s, the park became a popular gathering spot for counterculture movements, with music festivals and political rallies drawing large crowds to the amphitheater and surrounding areas. Redevelopment In recent years, the park has faced a number of challenges, including threats from development and climate change. In 2018, plans were announced to overhaul the park as part of a $1.45 billion flood protection project, which has been met with controversy and opposition from community members and activists. The project, known as the East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) plan, aims to protect the surrounding neighborhoods from flooding in the event of a major storm. The plan includes building a flood wall and raising the elevation of the park by several feet. One of the most controversial aspects of ESCR is the impact it will have on the park's trees and the people who value their pesence. The plan calls for the removal of more than 1,000 mature trees, some of which are over 100 years old, to make way for the construction of a flood wall and raised parkland. This has been a major point of contention for park advocates, who argue that the trees are an essential part of the park's ecosystem and a vital source of shade, clean air, and wildlife habitat. In addition, the removal of so many trees would have a significant impact on the park's aesthetics, changing the character of the space and removing an important element of its history. To address these concerns, the city proposed a replanting plan that includes the planting over 2,000 new trees, as well as shrubs and grasses. However, critics argue that the new trees will take years to grow to maturity and will not provide the same benefits as the old-growth trees that are being removed. The impact of the redevelopment plan on the trees also raises broader questions about the value of urban green spaces and the trade-offs involved in urban planning. While flood protection is a critical issue for the city, the removal of so many trees from a beloved public park raises questions about the priorities of city officials and decision making considerations. Tree Neighbors Several individual trees in the park that have become well-known and beloved by locals over the years. Alarge copper beech tree near the park's southern entrance estimated to be over 150 years old has affectionately been nicknamed by locals as "Old Man," and it has become a cherished symbol of the park's history and continuity. Another notable tree in the park is a large sycamore that stands near the amphitheater. This tree, known as the "Pirate Tree," has a distinctive split trunk that resembles a pirate ship's bow. It has become a popular spot for children to play and climb, and it is often decorated with homemade pirate flags and other treasures. Another notable tree was referred to as the "Mother Tree" by some locals. A large cottonwood, it stood near the amphitheater and was estimated to be around 80 years old. The Mother Tree was a beloved feature of the park and was known for its massive size and distinctive shape. It provided shade and shelter to park-goers and was a popular spot for picnics and gatherings. Unfortunately, the Mother Tree was among the trees that were slated for removal as part of the ESCR plan. Its removal was a significant blow to the community, and many residents and activists protested the decision. In response to the outcry, the city pledged to preserve a portion of the Mother Tree's trunk and incorporate it into a new seating area near the amphitheater. The loss of the Mother Tree underscores the importance of preserving and protecting urban green spaces and the connections that people form with the natural world around them.

0 Comments

Natural Areas Conservancy, a New York-based organization that works across the city to restore the city’s natural areas and to help New Yorkers discover the natural areas in their neighborhoods, recently hosted a symposium on “Forests in Cities: Nature-Based Climate Solutions”. A range of speakers, leaders from academia, non-profit organizations, and government, discussed the important yet undervalued ways of urban natural areas addressing climate change in cities is significant but has been traditionally undervalued. Discussed the following topics:

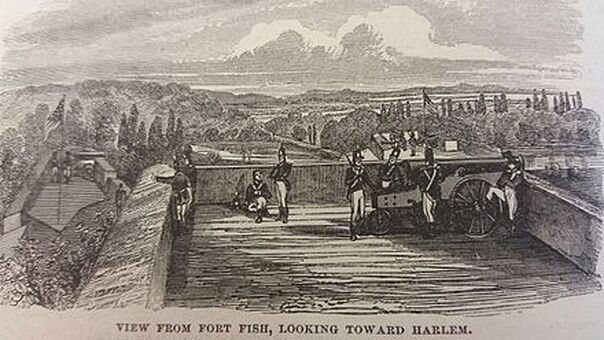

Among the key points raised were that more than 100 cities in the United States are managing forests, and 1.7 million acres in urban areas are natural areas, more than twice the acreage of Yosemite National Park. These areas play a critical role in climate change mitigation, including by sequestering carbon, cooling temperatures, and mitigating flooding and storm runoff. The carbon sequestered by trees in urban areas is the equivalent of the emissions of 500,000 cars per year. Essentially, they area an enormous carbon sink. The power of nature of provide climate solutions raises the question of how we will organize ourselves to leverage these benefits. Eighty-two percent of U.S. citizens live in cities. There is a need to mobilize around the issue of nature-based climate solutions. Yet, it can be challenging for people to care about nature if they have not experienced it. Thus, part of the change in the way we embrace nature as offering solutions needs to come from a change in people's relationship with nature. Natural Areas Conservancy has been a leader in restoring New York City's green areas and connecting urbanites with local natural areas and has been a significant voice supporting policies that benefit urban natural areas. One such initiative is the Climate Stewardship Act, which was introduced into Congress in September, 2019. If passed, the Act will fund the planting of 4.1 billion trees by 2030 and 16 billion trees by 2050. The trees would cover nearly 64 million acres and would capture more that two years of the U.S.'s greenhouse emissions, 13 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide, by the century's end. Four hundred million of these trees would be planted in urban areas, resulting in a cooling effect in the event of heatwaves and, in turn, a reduction in energy usage associated with air conditioning. Nature is at risk because of climate change--a nature offers solutions.  While we celebrate July 4th--Independence Day--with fireworks and barbecues, America's Revolutionary War still can seem like an event in the distant past. After all, 1776 was 243 years ago. Yet, traces of the war are apparent, vestiges written into, if not shaped by, the topography of the landscape itself--even in New York City. Central Park's steep bluffs overlooking the Harlem Meer were important strategic features during the American Revolution, their elevation and expansive views providing the site for the military fortifications Fort Fish, Fort Clinton, and Nutter's Battery, sites still on view today. During America's War of Independence, George Washington defended New York against invading British forces from this high-ground position that is now the northeast section of Central Park. The British defeated Washington in the area and built a series of fortification extending from the bluffs to the Hudson. In addition to Fort Fish, Fort Clinton, and Nutter's Battery, the British constructed a chain of blockhouses, the site of one of which is in Central Park's Northwoods, adjacent to 109th Street. Each of these locations was subsequently used by Americans to defend against the threat of British invasion from the north during the war of 1812. McGowan's Pass was another key topographic feature during the Revolutionary War in what is now Central Park. Located along the steep hill and switchbacks of what is now the park's East Drive north of 102nd street, it was a Hessian (conscripted German soldiers) encampment for much of the war, from 1776 to 1883. At the war's end, the Hessians and British retreated north through pass, while George Washington reentered New York through the pass. Gazing at today's runners and cyclists traversing topographies of Central Park that during the Revolutionary War were strategic locations suggests more than weekend warriors. One can, with a little imagination, time travel and conjure warriors of the American Revolution traversing the same terrain and making use of its features. Landscapes carry memory.  Horseshoe Crab. Photo by Anne W. York Horseshoe Crab. Photo by Anne W. York Far more than a concrete jungle, New York City boasts miles of coastline, which in late May and early June are the setting of an annual ritual that has taken place for nearly 500 million years, one of the oldest rituals to occur among animal species. During a recent stroll on Orchard Beach at Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx, I came across horseshoe crabs pulling up onshore. Intriguing looking, ancient creatures, they remind me of small tanks, able to ambulate while being fully protected by a hard carapace. Japanese legend too identifies the horseshoe crab with military symbolism. It was said that brave warriors who died honorably in battle were reborn as horseshoe crabs, with their shells like samurai helmets, forever traversing the ocean floor. Why were these creatures migrating onto the sand? Why now? Thanks to the Historical Signs Project of the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation, answering my questions -- and more -- was a nearby sign, "Horseshoe Crabs in New York City Parks, Orchard Beach - Pelham Bay Park." This is what it said about the fifth oldest species (after cyanobacteria, sponge, jellyfish, and nautilus), which has contributed greatly to medical science: Every May and June, horseshoe crabs emerge from Pelham Bay and Long Island Sound onto Orchard Beach in Pelham Bay Park. Female horseshoe crabs arrive on the beach to lay their eggs, with their male counterparts literally in tow. Males grasp onto the back of the female's shell using their specially adapted, hooked legs, sometimes two, three, or four onto one female. When they arrive on the beach, female horseshoe crabs dig a hold in the sand and lay up to 20,000 tiny olive-green eggs . The males then rush to be the first to fertilize. The process is heavily tied to the lunar cycle and its effects on the tides. The mating begins when the moon's force is strongest and the high tide allows the horseshoe crab to venture further onto the beach. As the force weakens, the water is never able to reach the eggs. Two weeks later, when the moon's force peaks again, the eggs are ready to hatch and the water sweeps the newborns into the sea. While this timing has provided protection from the sea, the eggs face other dangers. The thousands of protein-rich eggs provide a feast for hungry migrating birds, which can eat enough to double or even triple their body weight before moving on. Some birds are believed to time their migration to coincide with this mating ritual and its resulting source of nutrition. The horseshoe crab...has been around since before he dinosaurs.... This prehistoric creature may resemble a crab, but is actually more closely related to the spider and scorpion. While the horseshoe crab has a tough exterior that has helped its survival, it is one of the most harmless creatures on the seashore. Its high tolerance for pollutants has also allowed the horseshoe crab to thrive where other species have failed. When not swarming on the beaches in the spring, the horseshoe crab stays mainly on the ocean floor, feeding on mollusks, worms, and seaweed. In the winter, it burrows into the ocean sediment. While the lifespan of a horseshoe crabs in the wild is not clear, they have been known to live up to 15 years in aquariums. This "living fossil" plays an important role in modern medical science. Its blood contains Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL), which is used by scientists for the detection of bacterial toxins. Tests using LAL are required by the Federal Drug Administration for medications and vaccines. Blood from the horseshoe crab is also used to make a variety of products, from fertilizers and conch bait to hairspray and contact lenses. These uses have led to the overharvesting of the horseshoe crab and a decline of its population in the Atlantic. However, the ancient horseshoe crab can still be seen crawling onto the shores of the Bronx, at Orchard Beach, every year. This past weekend I had the privilege of guiding a forest therapy walk in collaboration with my friend and fellow guide Linda on behalf of Natural Areas Conservancy. The walk took place in Alley Pond Park in Queens. Alley Pond Park is the most ecologically diverse New York City Park. It includes salt marshes along Little Neck Bay to the north and forested areas to the south along Union Turnpike and contains the oldest living creature in New York City, the Queens Giant, a 350 year old tulip tree. The walk had a great turnout, including an appearance by local Council Member Barry S. Grodenchik, an advocate for local parks, a reminder that it takes a village to support our parks. There are few organizations working harder or more comprehensively to support our local parks than Natural Areas Conservancy, “a champion of NYC’s 20,000 acres of forests and wetlands for the benefit and enjoyment of all. [NAC’s] team of scientists and experts promote nature’s diversity and resilience across the five boroughs, working in close partnership with the City of New York.” What does it take to champion New York City’s Parks? With 20,000+ acres of natural areas, including more than 10,000 acres within NYC Parks (equating to half the size of Manhattan), there is much to do. Here are examples of just some of NAC’s work:

Photo: Jim McDonnell (2018) Photo: Jim McDonnell (2018) Water creates and destroys. It is vital for life, for humans and other animals (we who are mostly water) and for vegetation on which our lives and the lives of almost all other living creatures depend for food and oxygen. It is a source of delight, a tall glass of ice cold water quenching our thirst on a hot day, a cool shower cleansing off the sweat and grit of from a sweltering city day, and a glimpse of a shimmering river, bay or ocean offering a panorama that can fill us with a sense of beauty and awe. Yet, water also annihilates. It turns violent in its machinery of storms, with ravaging hurricanes and wall-of-water tsunamis inundating and destroying homes and possessions and endangering and ending our lives. Over years, water destroys the roofs over our homes. Over eons, it eats away at the land, eroding it to form canyons; as glacial ice, it pushes aside stone, carving grand valleys like giant earth moving equipment. We encounter water-as-destroyer with the arrival of hurricane season, and the 2018 season launched with Florence hitting landfall in the Carolinas this past weekend, swelling rivers, transforming streets into canals, uprooting trees, and destroying homes and lives. Floodwaters continue to rise, with the region’s water supply endangered by contamination from toxic pollutants. Yet, a few hundred miles to the north, with a high pressure system stalling the northward creep of the storm, water was offering its delights to a few dozen swimmers, including myself, participating in an open water event at Coney Island with CIBBOWS, Coney Island Brighton Beach Open Water Swimming, the “Triple Dip”, with options to swim 1, 2, or 3 miles. Despite the devastating conditions in the Carolinas, the conditions at Coney Island were splendid, with air temperature in the mid-seventies and water at a temperature in the low-70s and not unusually turbulent. Swimming at Coney Island offers an experience in contrasts, even separate from markedly different weather systems along the coast. Immersed off the coast in the open water, slicing through modest chop and current, and occasionally bumping into fish, one catches glimpses of the amusement park and its iconic rides: the Cyclone roller coaster, carousel, and Wonder Wheel, looking like giant toys. On the one hand, ocean water, so natural and elemental, and on the other hand, brightly colored attractions built for entertainment. Then again, the water offers its own ride, with wave motion rocking your body and the current redirecting your stroke. But if the amusement park Cyclone was abuzz with activity, so too was a real cyclone, making landfall to the south, and during the day’s swim at Coney Island, the duality of water—like the Hindu god Shiva, destroyer and benefactor—was on many of our minds. After all, it was only 6 years ago that Hurricane Sandy inflicted tens of billions of dollars of devastation in the New York area. Storm surges flooded streets, subways, and tunnels and terminated power for many communities, and we are still experiencing the storm’s effects. The flooded Cortland Street subway station opened just a few weeks ago, and the L train will soon shut down for repairs due to damage incurred from Sandy flooding. Other hurricanes continue to devastate in their aftermath: Maria in Puerto Rico, Harvey in Texas, and Katrina in New Orleans How to reconcile the contrasts in nature? On the one hand, water offered its delights to a group of folks opting for the voluntary adventure of a beach-side open water swim on a sunny day, with a view of a giddy amusement park; yet, a few hundred miles south, water was a force of monstrosity, putting lives at risk. Like the ebb and flow of tides, water gives and takes away. Wind, Water, Stone By Octavio Paz (1979) Translated by Elliot Weinberger Water hollows stone, wind scatters water, stone stops the wind. Water, wind, stone. Wind carves stone, stone's a cup of water, water escapes and is wind. Stone, wind, water. Wind sings in its whirling, water murmurs going by, unmoving stone keeps still. Wind, water, stone. Each is another and no other: crossing and vanishing through their empty names: water, stone, wind. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed