Heightened attention to early flower blooms, described in my previous blog, has awakened my visual awareness and made me more attuned to forms and structures everywhere. Lately I've been particularly attuned to surfaces. By "surfaces" I mean the outermost layer, perceived by sight and touch--boundaries and edges that define, separate, and connect. Consider the many ways to describe surfaces, the characteristics that define them, to name a few: smooth, rough, patterned, textured, hard, soft, straight, curved, color, symmetrical, matte, shiny, reflective. And often, surfaces become all the more intricate the closer one looks. What appears as smooth may in fact be comprised of grooves and particles, with infinite complexity. City life offers an opportunity to notice the surfaces of our built environment, the geometric, smooth facades of buildings, sidewalks, stairways, and interior spaces--walls, floors, ceilings, furniture. What a contrast these views are to the undulating, uneven and surprising surfaces of the natural environment, of trees, flowers and shrubs growing along streets and in parks, of rocks and water. Some say that the "Euclidean geometry" of our built environment impairs our "visual fluency", that we innately crave the visual complexity offered by natural environments, visual fields that feed our brains' ability to absorb complexity. Yet, it is worth considering that the materials that create our built environment derive from natural materials: wood harvested, stones gathered and cut, and metals mined and smelted, transformed from their natural state to be put to our use. On a micro-level, their true natural forms become apparent: the cellular structure of wood, and crystalline structure of metals and rocks. What began as an ordinary day transformed into sensory adventure as I tuned into the surfaces around me.

0 Comments

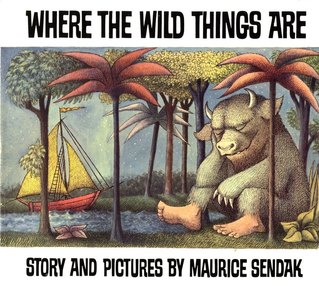

Shantanu Kuveskar, CC BY-SA 4.0 Shantanu Kuveskar, CC BY-SA 4.0 Each season offers its gifts to our senses, and with autumn our senses awaken to the powerful changes in nature around us. We observe the leaves changing color and falling to the ground, we hear crisp leaves underfoot, we feel a stronger breeze and cooler temperature, and deep within our bodies, with the waning daylight, perhaps comes a gnawing desire to retreat to our homes a little earlier and stay snug and warm, much like fellow creatures that hibernate. Our sense us smell awakens too to the change in seasons. What causes that rich “autumn smell”? In a recent article journalist Matthew Cappucci provides insights: Leaves are designed to produce “food” for the plant — glucose — through the process of photosynthesis. They take in six carbon dioxide and six water molecules at a time and, with a bit of sunlight, reshuffle them to form glucose and six oxygen molecules. That’s why plants are said to “purify” the air. They add breathable oxygen to it. But even though this reaction produces energy for the plant, it takes a lot of work to sustain. In the fall, when the energy needed to create the “food” outweighs the energy afforded to the plant by the food itself, the leaves are no longer needed — and with that, the tree bids them farewell. When the leaves fall, they die. As they take their last breath, they “exhale” all sorts of gases through tiny holes known as stomata. Among these compounds released are terpene and isoprenoids, common ingredients in the oils that coat plants. Terpenes are hydrocarbons, meaning their main ingredients are hydrogen and carbon. Pinene, a species of terpene, smells like — you guessed it — pine. It’s a main ingredient to the saplike resin that repairs the bark of conifers and pine trees. Occasionally, these gas molecules excreted by plants — known as volatile organic compounds — interact with variants of nitrous oxide. This can lead to ozone production, which can smell a bit like chlorine or the exhaust of a dryer vent. In addition to the release of gases contained within dying vegetation, two other effects contribute to the emotion-evoking scent that accompanies a northwest autumn breeze: decomposing plant matter, and pollutants trapped at the ground levels during the fall months. The soil in most parts of the world is rich in Geotrichum candidum, a fungus that causes rotting and decomposition of fruits and vegetables and dense plant matter. In fact, Geotrichum candidum has been sampled on all seven continents. This is just one of many species that erodes away as deceased organisms, the chemical reactions of which contribute to the smell of “fall.” Allow your senses to connect with autumn.  Photo by Nancy Kopans Photo by Nancy Kopans Nature is ever at work building and pulling down,… keeping everything whirling and flowing, allowing no rest but in rhythmical motion, chasing everything in endless song out of one beautiful form into another. – John Muir During a recent forest bathing walk a participant wondered whether “motion = life”. I have pondered this observation, thinking about how not everything alive is in obvious motion. Yet, on closer examination there is motion – a heartbeat, cellular activity, the vascular activity of plants. Perhaps it is this sense of “motion = life” that leads people to comment on how alive the city is, how it has energy, with its buzz of activity – people walking, taxis zooming, neon signs blinking -- like a giant organism. There are few better ways to experience a city and its whirl of motion than on a bicycle. On a bike one moves fast enough to get somewhere, but slow enough to see what’s around. And beyond seeing, there’s what’s experienced. There’s no glass or metal to separate us from surroundings, and with speed quickened from the pace of walking, senses become alert -- the sight of pedestrians stepping into a nearing intersection with the changing of a light, the feel of the breeze (even on a hot, muggy summer day), the sound of a siren somewhere. Streets become like a river, the bike like a kayak navigating white water. Being in motion, the turning of wheels propelled by the force of pedaling, seems to conjure the motion all around while making oneself a part of that motion too. There’s a sense of keeping time, the rhythmic motion of wheels spinning round, the rhythm of people walking, of cars moving, stopping at red lights, moving at green, creating a choreographed dance of people going places, everyone at their own rhythm, but collectively like a grand percussion symphony. The compactness of the city becomes apparent. Neighborhoods awkward to connect on a grid, such as a trip diagonally across town, or identified as geographically distinct zones (Uptown, Midtown, Downtown, East Side, West Side) can be traversed or connected within minutes, while allowing the rider to see all that is in between, stitching together the entire pattern of the city rather than starting at Point A and popping up at Point B, as in the case of a subway, with no clue of what’s in between. With this comes a feeling of independence, of being liberated from the constraints of the contained pods of subways and cars, with the vicissitudes of their interior space, and the slower pace of walking, even at the speed of a New Yorker still slower than on a bike, If distances are felt, so too are the city’s gradients. The paved-over hills and valleys that we are blind to when in a car, bus, or subway become apparent and experienced – a felt reading of the terrain. Biking puts the “hill” back in Murray Hill, Lenox Hill, and Carnegie Hill. And even in 94 degree soupy muggy weather, there’s a breeze. But if there’s freedom on a bike, there’s also a connection to civilization, and in this way biking in the city seems like a pure expression of what it is to be alive and human in a city. A bike after all is forged from metal, pure Vulcan (albeit from earth-sourced element) technology, and pairs beautifully with pavement for a smooth, human-propelled ride, a blending of the natural, ever-moving creatures that we are and technology. Although I’ve done a lot of road riding, including a self-guided cross country trip with a pal and a NYC-New Orleans self-guided trip with another pal, much of my riding these days is via Citibike, New York City’s bike share service. Citibikes are hearty 3-speeders with upright handlebars. They remind me of my childhood bike, with its banana shaped seat, handlebar basket, and plastic streamers radiating from the handlebar tips (how they moved in the wind!). What joy in that memory, awakened when I’m on a Citibike. My own Rosebud. I commute to—and when the daylight is long—from work by Citibike a few days a week. According to my Citibike app dashboard, I’ve gone on 605 rides, lasting collectively 266 hours (time much better spent than in a subway or taxi!), with aggregate mileage thus far of 1,988. That’s just about the distance from New York City to Cheyenne, Wyoming. There are days when I like to imagine that I’m on a stretch of road along that route. On a bicycle, imagination is free to roam.  Photo by Nancy Kopans Photo by Nancy Kopans The fourth nor'easter of the 2017-2018 winter season has hit. During a "pocket adventure" of a snowy morning wander through Central Park, I was reminded of a piece I wrote some years ago about a pocket adventure during another snowstorm, which happened to coincide with an apt exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History and performance at the Metropolitan Opera, and nods to my hero Max from Where the Wild Things Are, also mentioned in my previous post: ------ December 26 brings urban snow storm bliss to this woman who grew up reading tales of explorers of faraway places: nighttime cross-country skiing up Lexington Avenue, then into Central Park, breaking trail around the Reservoir bridle path. Trees groan in the wind and lightening zaps the sky bright for a moment. The snow bears down hard and drifts. By the time I come full circle on the bridle path, my tracks are gone. After twenty-five years of living in the neighborhood and frequenting the park, I am used to the variability of this place, how it changes with the seasons and times of day. But, this evening, it is eerily transformed. All alone in this dark and wind-howling space, I am transported to deep winter in New England, or if I let my imagination go farther, to a place more remote: Antarctica. I am in the company of the ghosts of Robert Scott and Roald Amundsen, whose voyages to the South Pole are chronicled in the exhibit now at the American Museum of Natural History and who perhaps, by some supernatural force and dark sense of humor, brought on this storm to enhance the exhibit’s verisimilitude. If I listen hard enough through the wind, I can will myself into hearing the explorers’ sled dogs yelping, stirred to life and excited by the storm. I complete my evening adventure with a ski down East 79th Street and return to my apartment, feeling lucky to have shelter. The next morning I awaken early to ski in the park while the snow still is pristine. Plows have been through overnight, clearing Central Park Drive and east-west pathways. But for this touch of civilization and the efforts of many now sleep-deprived snow clearing teams, all is quiet, still, and disguised by heaping drifts of snow. I am once again transported to a faraway place, like Max in Where the Wild Things Are, when his bedroom transforms into a jungle. Lost in the rhythm of skiing and day dreaming about being a part of Amundsen’s courageous team, I barely notice the stranger trudging by ski-less. As I glide past, he says, “I once skied to the opera!” I am stirred out of my snow-induced trance enough to reply, “I’m going tonight. La Fanciulla.” I smile inwardly at the appropriateness of this of all operas, with its snow scene and gun-slinging, frontier-woman heroine not dying of consumption, a rugged character perfect for the rugged weather. My response evidently strikes a chord. The stranger senses an opening and asserts, “What’s with the over the top Magic Flute? Too much for an opera buffa! What do they think it is, The Lion King?” He continues, “And that Anna Netrebko, she’s such a ham. I mean that Lucia, singing with her neck hanging off the stage! What next, singing standing on her head, just because she can?” With Scott and Amundsen in slow fadeout, I realize it’s not a moment to debate the virtues of spectacle for bringing in broader audiences. I agree with the stranger, noncommittally. It’s time to ski along. As I glide away, I think about how I love New York, still itself even when costumed in two feet of snow. I arrive home, and although it’s breakfast time, I have some hot soup, like Max.  Dressed in his wolf suit and wreaking havoc in his home, Max is sent to his room without any supper. Magically, his room transforms into a forest. Max sails to the land of the Wild Things, who eventually coronate him as their king, with a wild rumpus to celebrate. In time, Max tires of the land of the Wild Thing and sails back home. He returns to his room, where soup his mother has left for him is still hot. Alice tires of sitting by her sister Lydia along a riverbank and listening to her read a book without pictures when she notices a white rabbit scurrying by. Following after him down a hole she encounters a hookah-smoking caterpillar, the Cheshire Cat, the Queen of Hearts, Mad Hatter and others. On the verge of being beheaded, she finds herself back at the riverbank with Lydia. And in The Lion, the Witch, and The Wardrobe, the Pevensie children--Lucy, Edmund, Susan and Peter--enter the magical world of Narnia through what appear to be an ordinary piece of furniture. There they encounter Aslan the lion King, the White Witch, and others and grow into adulthood, only to one day tumble through the wardrobe back into the "normal" world and learn that no time has passed. Where the Wild Things Are, Alice in Wonderland, and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, remind us of the ability of imagination to expand time and experience. In what turns out to be very little little time at all, Max, Alice, and the Pevensie children encountered elaborate adventures, experience courage and fear, and grow--and, in the case of Alice, shrink too. Were all of these characters only dreaming? Children would question that assumption; they know that with a little imagination adventure can be found at almost any moment, and imaginary encounters can feel just as authentic, if not more so, than "normal" life. Can we as adults, in the context of our daily lives and our many responsibilities, and without relying on technological distractions, find moments to venture to where the wild things are, including our own inner wildness? How can we find the rabbit holes or wardrobes that enable us to discover liminal worlds that offer not only a break from the ordinary but also a chance to get in touch with aspects of ourselves, and perhaps more authentic aspects, that don't get a lot of attention? For Max, noticing trees growing in his room led him on his adventure. For Alice, it was a white rabbit in a hurry. And for the Pevensie children it was sensing the crisp cold of snow. While we may be many years from childhood, we too can use our senses and imagination to augment and enrich our daily lives, to discover "pocket adventures", and we can do it by noticing nature. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed