When the chill of winter arrives, you can either run the other way or embrace it. Having spent many years enjoying the outdoors in all seasons and weather, I aim for the latter and in this spirit spent the past week on a dog sledding and Nordic skiing camping trip in northern Minnesota. With temperatures well below zero and in the single digits, but also in the balmy teens, needs focus in on the basics: food and sufficient firewood with which to boil water and cook, the right clothing for staying warm and dry, and shelter-- in this case a bivvy sack for sleeping under the stars. The Boundary Waters are remote area that feels all the more remote in the winter. An area north of the "Laurentian Divide", raindrops and snow melt end up in the Arctic Ocean, rather than the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, or Pacific. Led by the fabulous outfitter Wintergreen, founded by Paul Schurke, a noted polar explorer whom we dubbed "Eighth Wonder of the Word" for his endurance, resilience, and intrepidness, the trip entailed traversing blissful miles of frozen lakes and boreal forests filled with black spruce and balsam furs, birch, and aspen. Along the way was evidence of local creatures -- snow tracks left by wolves, deer, moose, and snowshoe hares -- and continual admiration for our sled dogs, true professionals, each full of personality and eager to pull, dragging sleds carrying our heavy loads of equipment (with skiers breaking trail in the deeper snow). Inuit dogs are the domesticated breed closest to wolf; their wolfish selves emerging in their occasional canine-bearing snarls directed at one another to assert dominance. At the same time they respond like puppies when interacting with humans, basking in attention and rolling onto their backs for a stomach rub. In the remote frozen region, one's reliance on others becomes all the more apparent, an interesting irony in that one can feel most connected to other people in a wilderness environment. Arriving into the evening's campsite, we spread out to perform tasks assumed almost instinctually: gathering firewood, digging into the lake ice to create a water hole, setting up a fire pit on the ice, with a layer of logs underlying metal fire trays to separate the fire and ice. We cleared areas to set up our bivvy sacks, digging into the snow to shelter the bags from wind. And we tending to the sled dogs, transitioning them from the sled to hooking them up one by one on a line set up along the trees, removing their harnesses, and preparing their food. While the Boundary Waters are a world away from New York City, there was much that was elemental on the trip that translated to my urban home. If neighboring wolves and our sled dogs are pack animals, so too we humans form packs, finding community and interdependencies among one another, and even asserting--or encountering others asserting--alpha dominance. My return to New York City from the Great North Woods felt uncanny. The taxi that whisked me from the airport to home seemed confining and way to warm inside. To the driver's chagrin, I opened the window to feel the snap of cold and the breeze -- to breathe again -- and could almost imagine that I was being transported by dog sled across a frozen lake, rather than in a taxi on the crowded Grand Central Parkway. On arriving home, I took pleasure in having a warm bed and modern conveniences: indoor plumbing and a stove that didn't require gathering abundant firewood. At the same time that I appreciated the significant labor saved by these inventions, they also made me feel disconnected from the elemental features they deliver: fire at the turn of a knob; water at the turn of a handle. No hours spent scouring an island for firewood, with coordinated efforts to chop and saw fallen trees, drag them many yards to our fire pit and sort the wood into fire-starter twigs and birch bark, thicker branches, and logs. No continual chinking into the 2-foot lake ice to reach water. It all seemed too easy, and I pondered for a while what is lost when we receive such abundant resources with ease -- recognizing too how much is gained by not having to focus every day on basic survival needs. Having unpacked and run a load of laundry (more modern convenience magic!), I proceeded outside, ambling down Lexington Avenue, with each step sensing the breeze along the avenue as it touched the bare skin of my face and noting it felt as constant as the breeze encountered while traversing frozen lakes and forests on skis and dog sled. By some premonition, I felt a presence that impelled me to look up. And there, aloft on 73rd and Lex, was a Peregrine falcon, drifting on a thermal, a touch of wild in the metropolis, and a reminder of the wildness that persists if we just know where to look.

1 Comment

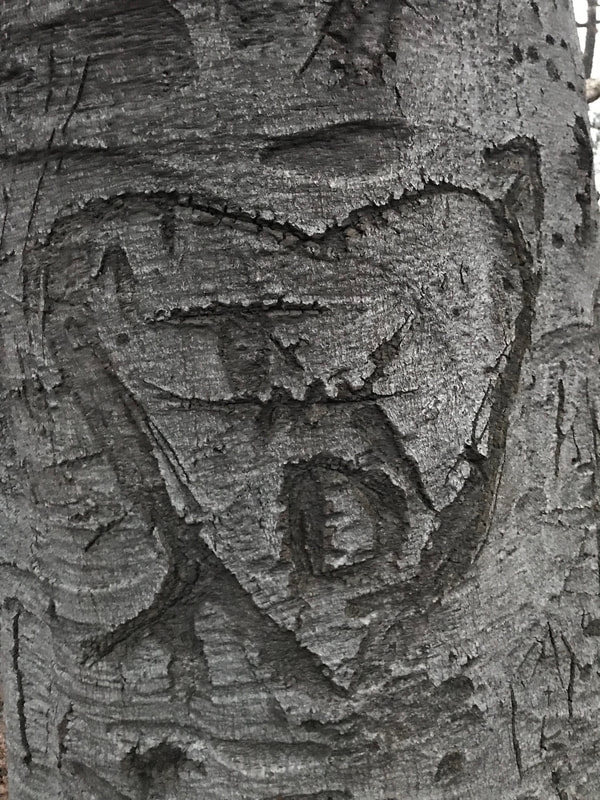

Trees invite expression of love, especially beech trees. With their smooth gray bark, it's difficult to find an older beech tree that does not have a heart with initials carved into its trunk--at least in Central Park.

Much as hearts are among the more popular tattoos inked onto human skin, the tendency to etch hearts onto the elephant hide-like bark of beech trees suggests that memorializing love comes from a place deep within us. There is something that impels us to mark our feelings of love in ways that pierce below the surface, perhaps because love itself is so deeply felt. Above are samples of hearts carved on beech trees in Central Park (alas, such etching harms the tree, inviting disease and if deep, disrupting the flow of nutrients). Did the love last? Did the lovers grow old together like the tree that display their affection? We will never know. But the expression of love lives on, preserved for decades on the bark of trees.  Luminescent, intricate photographic renderings of botanical forms -- "British Algae", otherwise known as seaweed -- appear in light blue and white against a darker blue background. This is the work of Anna Atkins, a long-obscured 19th Century botanist, artist, and pioneer in the application of photography to science. Atkins's work is on display through February 17 at the New York Public Library, Atkins applied the process of cyanotype, a cameraless photographic method utilizing light-sensitive paper to create in 1843 the first book illustrated exclusively with photographs. She donated the book, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, the Royal Society and dedicated it to her father, John Children, a fellow at the Royal Society. Children was friends with John Herschel, an astronomer and early photographic pioneer, who invented cyanotype in 1842 and introduced Atkins to the photographic medium. Atkins's application of photography to capture botanical images was a leap forward for scientific advancement. As noted in the NYPL exhibit: "In Renaissance Europe, artists' renditions exploded in popularity as the need arose for repeatable visual information to complement the printed word. The marked rise in the level of scientific inquiry from the 17th century forward paralleled a growing sophistication n these drawings and improved methods of distributing them. Among the most socially useful applications of art and science was the herbal, a genre of reference book on plants that describes their appearance as well as their medicinal, culinary or toxic properties. The hand of the artist, however, was not always in sync with the eye of the scientist, Rare was the individual who could reconcile the two. Difficulty emerged when the artist could not comprehend- or perhaps wasn't sympathetic to--the kind of information of greatest value to the botanist. Before British Algae, the only pictorial catalogues of botanical collections were illustrations with hand-rendered artists' impressions, or sometimes with actual dried plants affixed to their pages." The NYPL exhibit, the first dedicated to a full representation of Atkins's productions, not only offers insights into the history of photography and its application to science by a daring and innovative female scientist of the Victorian era, when gender roles usually relegated women to the domestic sphere. It also depicts flora in stunning detail and in ways that highly their exquisite beauty and symmetry. If cold weather is giving you the blues, step inside the NYPL to discover nature's blue prints. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed