|

It is a strange feeling to experience emptiness in the city. Streets, subways, and stores only recently packed with people are abandoned. The city's propulsive energy, its alchemy of people, traffic, and commerce, and with these, perpetual noise and motion, has dissipated amid the coronavirus lockdown. It wouldn't be surprising to see tumbleweed rolling across Broadway, as if in a deserted western town. Absent the hustle and bustle stand the stark horizontal grid of streets and verticality of architecture, like an empty set design awaiting its players, mirroring the empty sets of closed-down Broadway. The street grid, a rigid, fixed geometry that holds, harnesses, and thus enables the city's usual percussive beat and allows endless creative spark and serendipitous encounter rests now like an idling factory without purpose. The great emptiness resulting from coronavirus-mandated retreat indoors makes it evident that it is people who give the city its sense of vitality, who collectively transform it into a fantastic gigantic organism. As alienating and dehumanizing as a metropolis can sometimes be, we see in this time of crisis the capacity of closely packed people to create an environment that pulsates with energy. How we look forward to the time when that energy resumes.

0 Comments

Last week I was fortunate to attend and offer a small Forest Therapy walk following a symposium on The Transformative Properties of Horticulture, sponsored by the Madison Square Park Conservancy. The symposium featured inspiring speakers engaged in breathtakingly impactful work. Naomi Sachs, a professor of therapeutic landscape architecture at University of Maryland and founder of the Therapeutic Landscapes Network, a resource for gardens and landscapes that promote health and well-being, spoke about "restorative landscapes" and the importance of providing access to nature in healthcare settings. Hospitals are stressful places where patients and their visitors are at their most vulnerable. “Health”, she added, is not just “not being sick”. It is also about physical, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing, which is enhanced by natural environments. She described the notion of “restorative landscapes”, which are landscapes that promote health and wellbeing, and could be as simple as a fire escape or memorial--any place that where a person can find peace and solace. Sachs described the many scientific and medical studies supporting the beneficial impact of nature, including—among medical patients—more rapid recovery from surgery, reduced patient complaints, and reduced need for medication, and--among the general population--improved memory and attention and a reduction in ruminative thoughts. Gwenn Fried, Manager of Horticulture Therapy Services at NYU Langone Medical Center, then spoke about therapeutic horticulture in public spaces and underscored the value of targeting the certain populations that can most benefit from it, including:

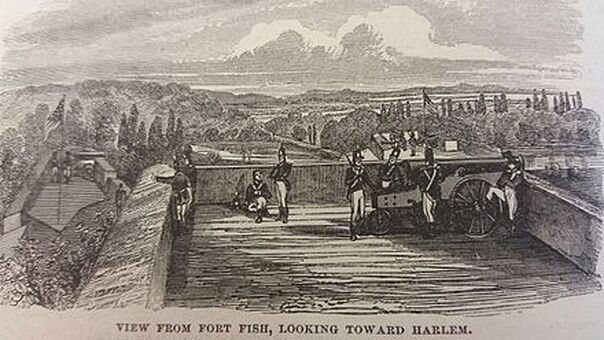

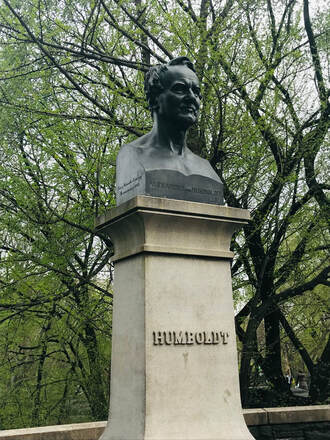

Regina Ginyard and Jenn Hertzell then engaged the audience in a networking activity focused on green spaces that give people joy. Ginyard is a founding member of Black Urban Growers (BUGS), an organization committed to "building networks and community support for growers in both urban and rural settings." Jenn Hertzell is a Bronx-based farmer and founder of At the Rood: An Herbal Eastery, Farm, and Apothecary that exists to create opportunities for people of the African Diaspora to hear their relationships with their bodies and with the earth. How fortunate we are that scholars and practitioners like Sachs, Fried, Ginyard, and Hertzell are improving lives through the transformative properties of horticulture. Stay tuned for my next blog entry to learn about what Amos Clifford said at the conference.  When planes struck the Twin Towers 18 years ago, New Yorkers and the world witnessed the perverse deployment of one type of human invention—airplanes—against another—skyscrapers. Of course, it was not the human-engineered aeronautic and architectural innovations themselves that resulted in the horrific loss of life, but rather al-Qaeda’s heinous scheme to appropriate them for harm. Yet, the scale of loss could not have been achieved without the capabilities made possible by human innovation. And, while we know that airplanes and skyscrapers derive from metals and petroleum harvested from the Earth, these materials, once smelted, shaped, and refined on an industrial level, hardly appear recognizable as “nature”. On September 11th we witnessed a Frankensteinian deployment of natural resources. What a contrast to that sinister application of human invention is the Ground Zero Memorial. With water cascading into hollowed imprints of the former sites of the two towers, names of the murdered etched into stone, and trees interspersed along the pavement, the memorial site brings together sustaining elements of nature: water, rock, and trees. I do not know what theories underlie the planner’s vision for the memorial site, but with my office just a few blocks away, I frequently stroll through the site and am regularly taken by how comforting it is. The continual rush of the sound of falling water as it catches the daylight; the solidity of stone holding in perpetuity the names of the deceased; and the color and fragrance of shade-providing trees, along with the musical sounds of the birds they host, offer strong reminders of the solace offered by elemental nature, particularly in contrast to technology gone rogue.  While we celebrate July 4th--Independence Day--with fireworks and barbecues, America's Revolutionary War still can seem like an event in the distant past. After all, 1776 was 243 years ago. Yet, traces of the war are apparent, vestiges written into, if not shaped by, the topography of the landscape itself--even in New York City. Central Park's steep bluffs overlooking the Harlem Meer were important strategic features during the American Revolution, their elevation and expansive views providing the site for the military fortifications Fort Fish, Fort Clinton, and Nutter's Battery, sites still on view today. During America's War of Independence, George Washington defended New York against invading British forces from this high-ground position that is now the northeast section of Central Park. The British defeated Washington in the area and built a series of fortification extending from the bluffs to the Hudson. In addition to Fort Fish, Fort Clinton, and Nutter's Battery, the British constructed a chain of blockhouses, the site of one of which is in Central Park's Northwoods, adjacent to 109th Street. Each of these locations was subsequently used by Americans to defend against the threat of British invasion from the north during the war of 1812. McGowan's Pass was another key topographic feature during the Revolutionary War in what is now Central Park. Located along the steep hill and switchbacks of what is now the park's East Drive north of 102nd street, it was a Hessian (conscripted German soldiers) encampment for much of the war, from 1776 to 1883. At the war's end, the Hessians and British retreated north through pass, while George Washington reentered New York through the pass. Gazing at today's runners and cyclists traversing topographies of Central Park that during the Revolutionary War were strategic locations suggests more than weekend warriors. One can, with a little imagination, time travel and conjure warriors of the American Revolution traversing the same terrain and making use of its features. Landscapes carry memory.  Alexander von Humboldt statue near Central Park Alexander von Humboldt statue near Central Park Inconspicuously situated at Central Park West and 77th Street stands a statue of Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), largely forgotten in the English-speaking world. As we approach Earth Day it is timely to consider the impact of this extraordinary polymath who invented the concept of nature's inter-connected forces and unity. At a time when Enlightenment philosophers were still grounded in Aristotle's view that "nature has made all things specifically for the sake of man" Humboldt saw the natural world as an interconnected, fragile web of life. Humboldt's textual works, Personal Narrative, Views of Nature, and Cosmos, as well as political essays about the colonies, and his maps and graphical depiction of climate zones, inspired scientists, leaders, poets, and thinkers including Johann von Goethe, Charles Darwin, Thomas Jefferson, Simon Bolivar, Jules Verne, William Wordsworth, early environmentalist George Perkins Marsh, Erst Haeckel who term Humboldt's discipline "ecology", Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. Entire philosophical and literary movements--German Idealism, Romanticism, and Transcendentalism--can trace their lineage to Humboldt and he revolutionized fields as wide ranging as agriculture, meteorology, zoology, geology, hydrology, and botany. Over 300 plant and 100 animal species are named after him, as are minerals, mountains, geologic formation, glaciers, waterfalls, bays, state and national parks, moon craters, and an asteroid--more than are named after anyone else. At the source of Humboldt's influence was his relentless energy and curiosity, which in the early 1800s led him to travel widely to places where few Europeans had traveled before to conduct hands-on scientific experiments, map geologic characteristics, and collect and record botanical samples. With collections of the latest instruments, ranging from telescopes and microscopes, to barometers and pendulum clocks and compasses, he traveled 1700 miles of Venezuela's Orinoco River to the Amazon River basin, across Cuba, Mexico and Peru, (where he climbed Mount Chimborazo, an inactive volcano of nearly 21,000 feet) and across the mountains of Kazakhstan. From evidence accumulated during his travels, he pieced together systemic patterns, similarities, and connections across contents, inventing the classification of plants by climate zones rather than taxonomy. Observing the coastal matching of Africa and South America, he sensed an ancient connection between the continents that presaged our understanding of plate tectonics. Humboldt also identified the devastating ecological consequences of deforestation, ruthless irrigation, and cash crop agriculture, decrying the impact on habitats of man's "insatiable avarice”. Moreover, Humboldt sensed and observed nature not only empirically but viscerally and emotionally. "Nature", he wrote to Goethe, "must be experience through feeling." In her thrilling and meticulously researched biography of Humboldt, The Invention of Nature, (2015), Andrea Wulf reminds us of the contributions of this influencer of influencers and restores his rightful place among the pantheon of scientists. With the arrival of Earth Day, consider the impact of Humboldt; there are few better ways to do so than through Wulf's magnificent biography.  Heightened attention to early flower blooms, described in my previous blog, has awakened my visual awareness and made me more attuned to forms and structures everywhere. Lately I've been particularly attuned to surfaces. By "surfaces" I mean the outermost layer, perceived by sight and touch--boundaries and edges that define, separate, and connect. Consider the many ways to describe surfaces, the characteristics that define them, to name a few: smooth, rough, patterned, textured, hard, soft, straight, curved, color, symmetrical, matte, shiny, reflective. And often, surfaces become all the more intricate the closer one looks. What appears as smooth may in fact be comprised of grooves and particles, with infinite complexity. City life offers an opportunity to notice the surfaces of our built environment, the geometric, smooth facades of buildings, sidewalks, stairways, and interior spaces--walls, floors, ceilings, furniture. What a contrast these views are to the undulating, uneven and surprising surfaces of the natural environment, of trees, flowers and shrubs growing along streets and in parks, of rocks and water. Some say that the "Euclidean geometry" of our built environment impairs our "visual fluency", that we innately crave the visual complexity offered by natural environments, visual fields that feed our brains' ability to absorb complexity. Yet, it is worth considering that the materials that create our built environment derive from natural materials: wood harvested, stones gathered and cut, and metals mined and smelted, transformed from their natural state to be put to our use. On a micro-level, their true natural forms become apparent: the cellular structure of wood, and crystalline structure of metals and rocks. What began as an ordinary day transformed into sensory adventure as I tuned into the surfaces around me.  Luminescent, intricate photographic renderings of botanical forms -- "British Algae", otherwise known as seaweed -- appear in light blue and white against a darker blue background. This is the work of Anna Atkins, a long-obscured 19th Century botanist, artist, and pioneer in the application of photography to science. Atkins's work is on display through February 17 at the New York Public Library, Atkins applied the process of cyanotype, a cameraless photographic method utilizing light-sensitive paper to create in 1843 the first book illustrated exclusively with photographs. She donated the book, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, the Royal Society and dedicated it to her father, John Children, a fellow at the Royal Society. Children was friends with John Herschel, an astronomer and early photographic pioneer, who invented cyanotype in 1842 and introduced Atkins to the photographic medium. Atkins's application of photography to capture botanical images was a leap forward for scientific advancement. As noted in the NYPL exhibit: "In Renaissance Europe, artists' renditions exploded in popularity as the need arose for repeatable visual information to complement the printed word. The marked rise in the level of scientific inquiry from the 17th century forward paralleled a growing sophistication n these drawings and improved methods of distributing them. Among the most socially useful applications of art and science was the herbal, a genre of reference book on plants that describes their appearance as well as their medicinal, culinary or toxic properties. The hand of the artist, however, was not always in sync with the eye of the scientist, Rare was the individual who could reconcile the two. Difficulty emerged when the artist could not comprehend- or perhaps wasn't sympathetic to--the kind of information of greatest value to the botanist. Before British Algae, the only pictorial catalogues of botanical collections were illustrations with hand-rendered artists' impressions, or sometimes with actual dried plants affixed to their pages." The NYPL exhibit, the first dedicated to a full representation of Atkins's productions, not only offers insights into the history of photography and its application to science by a daring and innovative female scientist of the Victorian era, when gender roles usually relegated women to the domestic sphere. It also depicts flora in stunning detail and in ways that highly their exquisite beauty and symmetry. If cold weather is giving you the blues, step inside the NYPL to discover nature's blue prints.  A recent blog focused on the Atlantic Flyway and the great spring migration of birds from tropical regions to northern breeding grounds. It's thrilling to witness the many species of birds that pause in our urban parks to rest and refuel. Thinking about birds' great aerial passage is also an opportunity to consider for a moment a birds' eye view. Places--many familiar to us when we are dwelling or moving within them--can look vastly different from overhead. Patterns emerge and one can't help develop an awareness of the interconnections among localities and regions across the earth. Artist Ben Grant explores this perspective in his book Overview. What began as an Instagram project is now a book with more than 200 breathtaking, high definition satellite photographs of industry, agriculture, architecture, and nature highlighting uncanny patterns and the impact of human existence. Says Grant, “From a distant vantage point, one has the chance to appreciate our home as a whole, to reflect on its beauty and its fragility all at once." Grant's book is well worth perusing and exploring. His work not only offers perspective on interconnections across landscapes and the human impact on our planet; it can inspire us to be aware of what an overview perspective might offer us in our current location--how our familiar surrounding buildings, blocks, avenues, and parks look from above. We can take time to imagine this perspective, and we also can explore the perspective Google Maps satellite view offers as a way to notice our environments from overhead. Beyond viewing location from above, we can consider the overviews available to us on a smaller scale, from our own, human vantage points--the forms and patterns observable to us at ground level as we move about or just pause to take it in. I think about a lovely New England lake where I enjoy swimming during the summer. How thick and robust its underwater vegetation becomes by mid-summer, with tendrils billowing in the murky water in a spectrum of shades of green, from deep olive to sweet pea. Skimming the surface stroke after stroke while gazing down through my goggles, I lose my sense of scale and imagine myself to be in flight, soaring through the air while peering down on a vast mass of flora below, a primeval jungle or forest. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed