Photo by Richard Lee on Unsplash Photo by Richard Lee on Unsplash Running around the Central Park Reservoir in the warmer months, I often eye the milkweed plants along the north side of the path, wondering when the monarchs will arrive. These beautiful orange and black-patterned butterflies, seemingly delicate, make an epic annual migration over four generations in the course of a year. To my delight, this morning I noticed a number of monarchs, likely the year’s third generation. Averaging 50 miles a day for four to six weeks, monarch Generation 1 begins its migration in early September from as far north as Canada and travels as far as 2,100 miles to cool regions east of Mexico City. Arriving by the end of October, they hibernate until March, when they awaken, mate, and migrate to the Southern United States where they lay their eggs on milkweed and die. Generation 2 hatches, feeds, metamorphoses, and migrates north where it lays eggs, reaching the New York City area in late June. Generation 3 survives for 4-6 weeks, into late July/mid August, the monarchs we observe now around New York City. Their offspring, Generation 4, will arrive in Canada by August, where they will store energy to prepare for their September flight to Mexico. Milkweed offers monarchs important protection. Monarch larvae ingests the milkweed leaves and with them the plants toxins, which are poisonous to monarch predators, such as birds. On eating a monarch, birds learn of the toxin, vomiting up the butterfly and subsequently avoiding ingesting it. Other species of butterfly even mimic the monarch’s colors, nature’s way of helping them avoid predators who may confuse them with monarchs. Milkweed might look like an innocuous plant, standing without fanfare in a patch along the Central Park Reservoir. It takes on a different level of significance when one thinks about its role in the epic annual, multigenerational migration of monarch butterflies

0 Comments

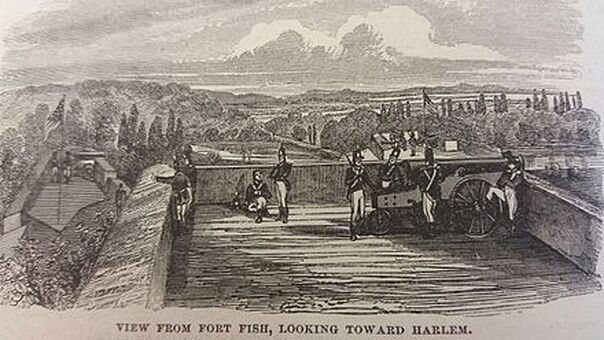

My "shadowflection" in Forest Park, Queens My "shadowflection" in Forest Park, Queens Shadows evidence physical presence--the instantiation of our bodies and of other creatures and structures. Bathed in daylight, our corporeal forms have the power to block the Sun's rays and cast dark reflections on the ground, what David Abram calls our "shadowflection". Even nighttime, as Abram notes, is nothing other than a hemisphere of the Earth enveloped in its own shadow. So too, shadows remind us of the sun's presence, and our position relative to it as we stand upon the Earth, our orbital home in continual motion. As the Sun migrates from low on the eastern horizon in the morning, to overhead, to low on the western horizon in the evening, our shadowflections shapeshift by the hour and season. Transitioning from elongated versions of ourselves, as if we were giants standing on the earth, to squat, to long again, they remind us of the continual motion of the Earth relative to the Sun, and perhaps other cycles and changes our bodies experience over the cycles of days, months, and years. And far more than a two-dimensional surface-restricted image, shadows have three-dimensional depth. Writes Abram in Becoming Animal: "My actual shadow is...more substantial than that flat shape on the paved ground. That silhouette is only my shadow's outermost surface. The actual shadow does not reside primarily on the paved ground; it is a voluminous being of thickness and depth, a mostly unseen presence that dwells in the air between my body and that ground. With the summer sun high in the sky, it is prime time for shadowflections, reminders of the our ever-present connection with the Sun, as the Earth turns and turns.  While we celebrate July 4th--Independence Day--with fireworks and barbecues, America's Revolutionary War still can seem like an event in the distant past. After all, 1776 was 243 years ago. Yet, traces of the war are apparent, vestiges written into, if not shaped by, the topography of the landscape itself--even in New York City. Central Park's steep bluffs overlooking the Harlem Meer were important strategic features during the American Revolution, their elevation and expansive views providing the site for the military fortifications Fort Fish, Fort Clinton, and Nutter's Battery, sites still on view today. During America's War of Independence, George Washington defended New York against invading British forces from this high-ground position that is now the northeast section of Central Park. The British defeated Washington in the area and built a series of fortification extending from the bluffs to the Hudson. In addition to Fort Fish, Fort Clinton, and Nutter's Battery, the British constructed a chain of blockhouses, the site of one of which is in Central Park's Northwoods, adjacent to 109th Street. Each of these locations was subsequently used by Americans to defend against the threat of British invasion from the north during the war of 1812. McGowan's Pass was another key topographic feature during the Revolutionary War in what is now Central Park. Located along the steep hill and switchbacks of what is now the park's East Drive north of 102nd street, it was a Hessian (conscripted German soldiers) encampment for much of the war, from 1776 to 1883. At the war's end, the Hessians and British retreated north through pass, while George Washington reentered New York through the pass. Gazing at today's runners and cyclists traversing topographies of Central Park that during the Revolutionary War were strategic locations suggests more than weekend warriors. One can, with a little imagination, time travel and conjure warriors of the American Revolution traversing the same terrain and making use of its features. Landscapes carry memory. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed