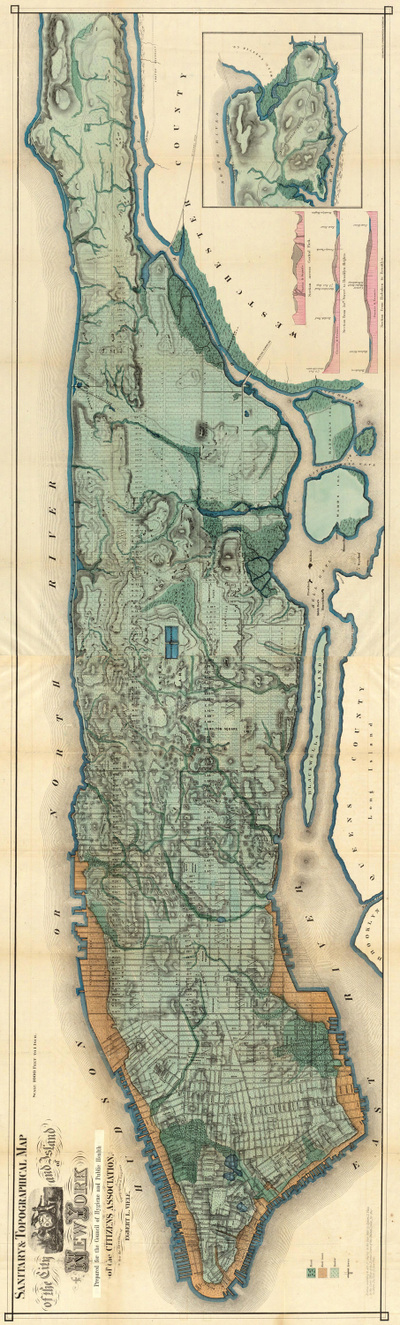

Egbert L. Viele's "water map" of 1874 Egbert L. Viele's "water map" of 1874 A New Yorker from the 1700s with an eye for watercourses returning today would notice much that is similar to 300 years ago. The Hudson, East, and Harlem rivers still surround Manhattan like a moat surrounding a castle, although landfill has altered the Hudson coastline along the southern tip of Manhattan and the Harlem River was expanded in the 1890s to traverse the tidal straight that separated Manhattan and the Bronx. Newtown Creek still separates what are now Brooklyn and Queens, and the Arthur Kill flows between New Jersey and Staten Island. Flushing and Little Neck bays still border northern Queens, and the Atlantic Ocean borders Brooklyn and Staten Island, leading through the Verrazano narrows to one of the great natural harbors, even if much of the shipping traffic has located to Elizabeth, New Jersey. But for all the still-visible waterways bordering New York City and demarcating its boroughs, much would appear different. Countless swamps, streams, springs, and ponds have been altered. Some still exist, but have been tamed by engineering and relegated subterranean realms, becoming part of New York City's sewer system. Perhaps most notable to our visitor would be the disappearance of the Collect Pond, the source of fresh water for Manhattan’s early European settlers and the Lenape people. What was once a place of drinking water is now a place of law and order. 60 Centre Street, the New York County Courthouse, was constructed over the pond's site, with pumps continually at work to prevent basement flooding. The 2014 redesign of "Collect Pond Park", near the courthouse and featuring a reflecting pool, now highlights this important water resource which was submerged in 1825. Like the Viele map, shown here and completed in 1874, the Nicolls map, completed in 1668 and referenced in John Kieran's 1959 book A Natural History of New York, shows numerous streams traversing Manhattan. As Kieran notes, "the Saw Kill, ran from what is now Park Avenue in the East River at about 75th Street. Montague's Brook ran from what is now 120th Street and Eighth Avenue in a zigzag course to enter into the East River at about 107th Street. It even had an island in it between Lexington and Third Avenues.... Minetta--or Manetta--Brook wandered through the Greenwich Village area...." To put it mildly, watercourse were abundant throughout New York City, and they still are, even if they aren't readily visible. In his terrific website and other writings intrepid urban explorer Steve Duncan identifies hidden watercourse throughout New York City. He notes that Manetta Brook now runs through a 12-foot wide sewer tunnel under Clarkson Street; the spring-fed Collect Pond, described above, in turn fed the marshland over which now sits Canal Street, which in turn became New York's first underground sewer; Sunfish Pond was located between what is now Madison and Lexington Avenues and 31st and 32nd Streets, with Sunfish Creek flowing from the pond to the East River. Tibbetts Brook, which ran near what would become Van Cortland Park in 1899, became what is now the largest sewer line in the Bronx, with the mill pond created when Jacobus Van Cortland dammed the brook in 1699 now a decorative pond in the park. Freshwater resources like Sunswick Creek in Queens and Wallabout Brook in Brooklyn are among the many other waterways that helped make the New York area habitable. Hidden Waters of New York City, by Sergey Kadinsky, also describes New York City's many waterways. Manetta Brook, he writes, is thought to derive from the Algonquin term "manitou or "spirit". Although the brook is now submerged, Minetta Triangle, a small park in Greenwich Village, depicts images of trout along its paths, homage to fish once found in the brook. The location of the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir was once a freshwater wetland from which a branch of the Saw Kill River drained. Signals and indicators of once-visible watercourses remain in place names: Spring Street, Canal Street, Water Street, to name a few. And, though submerged and encased underground, often through marvels of 200-year old brickwork, hidden watercourses routinely challenge urbanization and with it our sense of our own primacy and control over nature. From the early days of New York City's urbanization to present, development plans have been challenged by underground water: Manetta Creek challenging construction in Greenwich Village; the original Waldorf Astoria requiring continual pumping to contain seepage from an underground pond; the renovation of multi-million dollar townhouse on Manhattan's Upper West Side threatened by an underground stream; and according to Duncan buildings near Washington Square Park (2 Fifth Avenue and 33 Washington Square West) once housed fountains displaying water from underground springs. Even in a place as urbanized as New York City, nature courses throughout, submerged underground but still forcefully present, like primal, subconscious thoughts. Skilled engineering may tame and contain New York City's watercourses, but continual effort is needed to control what is ultimately a force bigger than ourselves.

0 Comments

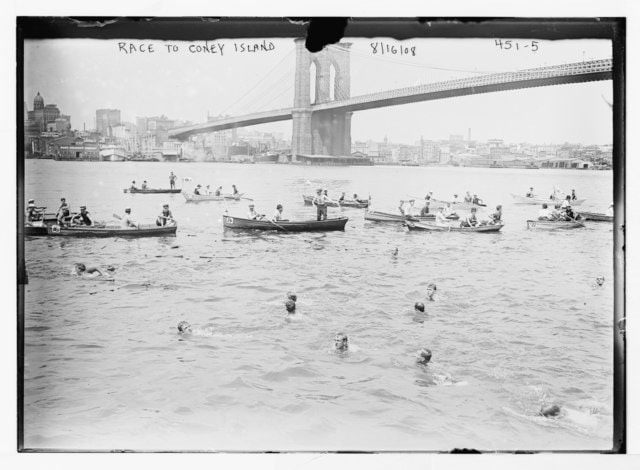

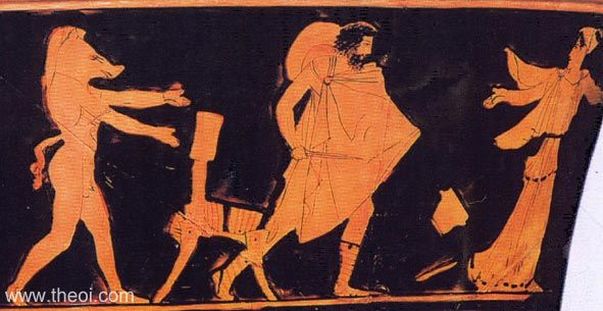

In my previous blog I described the feeling of swimming beneath the George Washington Bridge, the pairing of the mighty Hudson’s natural forces in perpetual ebb and flow and the stately, static grandeur of the human-engineered bridge. And I too was in motion at the nexus of the two, attuned with full sensory capacity to their majesty and interrelationship, witness to a linkage of two interdependent force fields. Few structures embody a human-nature connection more than bridges. To state what is obvious though perhaps often overlooked as we become inured to these fixtures of transportation systems, bridges exist to overcome obstacles imposed by nature. Wherever a bridge exists, so too exists a natural feature that poses a challenge to humankind, whether it be a river, bay, wetland, or valley. “Vaulting the sea”, as Hart Crane said in the poem, To Brooklyn Bridge. Bridges are human-engineered solutions to connect areas whose separateness was eons in the making. They span gaping ravines created by forces of uplift and separation, valleys carved by glaciers, the steady erosive forces of rivers, and bays created by advancing seas. The proportion, elegance, and mathematical symmetry of bridges embody laws of nature, defying gravity and load weight, whether from people, vehicles, or snow. Consider the compression-driven stability of arch bridges, where the weight of and atop the bridge is driven down to the ground, which in turn counters that force, and reinforces the bridge’s strength. So perfect are these structures that 2,000 year old Roman aqueducts still stand. Bridges range from the simplest wooden log across a stream or rope suspension solutions created by the Incas to traverse steep ravines, to the most sophisticated feats of metallic engineering. Bridges can be regarded as a type of magic, erasing impediments created by nature. If medicine makes use of plant-derived potions to cure illness, bridges make use of human-leveraged natural laws of physics to overcome geographic features that separate places. They are transitional spaces, in equal parts a way to and a way from. Employing laws of physics--arches and suspension--and nature’s materials--stone, wood, and metal--bridges at once demarcate and erase the separateness nature has wrought and in so doing offer a hint of the uncanny. Perhaps, then, it’s no wonder that folklore and myth are replete with disturbing creatures inhabiting watery edge-spaces: trolls, both helpers and troublemakers that first appeared in Scandinavian folklore and dwell under bridges or in other peripheral spaces; the fearsome and fanged multi-headed Scylla, transformed from a flirtatious maiden by Circe, and enemy of sailors passing by her in a narrow Mediterranean channel; or the dragon Grendel, describe in Beowulf as dwelling in a swamp at the edge of King Hrothgar’s kingdom. In the case of New York City, bridges span waterways whose origins date back hundreds of millions of years ago, when smaller continents collided into a supercontinent, which then rifted apart, creating a continental margin at what is now the Hudson Valley. Subsequent collisions, the absorption of a volcanic island arc, and the relatively recent (concluding 10,000 years ago) scouring of the land by glaciers carved the Hudson Valley further and left behind a moraine that shaped and created New York City’s bays and inlets, and even the Long Island Sound, flowing into the East and Harlem Rivers. Bridges not only span the remnants of millions of years of geologic activity; they occasionally take advantage of them. The George Washington Bridge was built in its location, with the steep Palisades on the west side of the river and Washington Heights on the East side, in part to take advantage of the cliffs left in place by ancient geologic activity, which eliminated the need for lengthy approach ramps to avoid interfering with maritime traffic. Spanning Newtown Creek, the Gowanus Canal, and the Hutchinson River; connecting City Island and Rockaway; and connecting Queens to the Bronx, Brooklyn to Staten Island and Staten Island to New Jersey, there are over 60 bridges in New York City. They range from arch bridges, to suspension bridges, to draw bridges, to one of four "retractable" bridges in the country. Manhattan is linked to neighboring boroughs and New Jersey by 20 bridges, the oldest of which, the High Bridge, which crosses the Harlem River and links the Bronx and upper Manhattan, was initiated by the need to transport water from upstate resources to the growing metropolis of Manhattan. Constructed in in 1848 as a stone arch bridge, the High Bridge looks like a Roman aqueduct. It took 35 years for the next bridge to be completed, the Brooklyn Bridge, a marvel of engineering that reinvented suspension bridge engineering by bundling multiple strands of steel cable, considerably enhancing the strength and load-bearing capacity of the bridge. From simple to grand, crossing small creeks and powerful rivers, New York City’s bridges not only connect distinct locations. They also tell a story about the natural geography they inhabit.  Bain News Service, publisher, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Bain News Service, publisher, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Hudson River, East River, Harlem River--Manhattan, as you know, is an island. But how often do we notice the waterways surrounding it and consider not only their presence, but the ebb and flow of their currents, their temperatures and micro-temperatures, and the ways they intersect? The density of Manhattan--with block after block of sky scrapers often blocking the horizon from view--contributes to waterway blindness, as does the legacy of Robert Moses’ city planning, which privileged cars over pedestrians by locating highways along the scenic margins of Manhattan. Many of us can go entire days, including commuting to and from Manhattan, without even seeing a waterway. Open water swimming offers a way to sense directly the powerful and magnificent waters surrounding our city, waterways created millennia ago that define Manhattan's island structure yet stand in sharp contrast to its built environment. Recently, a number of news articles have brought attention to Manhattan open water swimming, including articles about Ira Gershenhorn, Hudson River swimmer and clean water advocate; Jaimie Monahan, a New Yorker and champion open water, ice, and winter swimmer who aims to set a record as the fastest person to compete six marathon swims on six continents within 16 day; and the potential for creating a swimable beach on Manhattan as a way to escape the summer heat. Over the years, I have swum (not very fast) in a number of local open water events, including two four-person relays around Manhattan, several 6K “Little Red Lighthouse” swims in the Hudson, several swims around nearby smaller islands (Governors’ Island and Liberty Island), a 4-miler across the Long Island Sound, and a 3-miler across the Hudson at the Tappan Zee Bridge. This was in addition to out of town events, including 10 and 6 mile swims on Lake Memphremagog on the Vermont-Canada border, and crewing for various swims, including for a remarkable 15 year old swimming the 17-miles from Sandy Hook, New Jersey to Manhattan’s Battery. The local swims connected me with New York City’s surrounding waters, and as a result I never look at the waters the same way. Driving or biking along the Hudson in Manhattan, I notice that it is at times calm, and at other times ferocious. I notice areas of flatness, and areas of turbulence. Driving on the FDR, or over the 59th Street Bridge, I notice the racing tidal force pushing the East River northward. Swimming in nearby waters has attuned me to the wildlife of the waters, environmental conditions, and the impact of weather on the waters. The Little Red Lighthouse swims in the Hudson—the lighthouse is below the George Washington Bridge, on the East Side of the Hudson and was a subject of a lovely children’s book—ran north-to-south or south-to-north, depending on the in-bound and out-bound tide (the Hudson, as noted in an earlier blog, is a tidal estuary, with saline effects reaching 150 miles north to Troy, New York). The wave motion of a south–to-north swim on a windy day was particularly memorable, with the northward pull of the tide intercepting the southward pull of the current. Mr. Powell, my high school physics teacher, could have drawn a beautiful graph of the resulting wave motion of these two forces. Swimming in it required modulating stroke and breathing to this dual pattern, not unlike dancing to a complex beat. The Manhattan Marathon swims offered an opportunity to distill the differences in Manhattan’s three waterways: the East River, with the mix of currents at Hell’s Gate, where catching the wrong current would send one to the Long Island Sound yet hugging the Manhattan shoreline would add significant distance (I am forever grateful to my accompanying kayak guide for skillfully navigating that water); the relative calm of the Harlem River, which felt like a lazy river in a rural setting; and the sublimity of the Hudson, broad and powerful, where swimming with the tide could result in a pace of 6 miles an hour—in other words, like flying in the water or embodying Michael Phelps. Swimming under the George Washington Bridge, with a view of the bridge’s underside and a sense of proportion of its giant supporting stanchions ignited a sense of awe for the breadth and force of the Hudson and the human ingenuity to build such a structure. The pull of the water, the sense of passage under the bridge, its bold static arch and sentinel-like stanchions a contrast to the movement within movement of the water in which I was immersed and sensing with my full body (no wetsuits), and the rhythm of my arms stroking, legs kicking, and torso, head and neck rotating for breath, awakened a sense passage. The passage was not only a geographical transition into the waters south of the bridge, the home stretch toward Manhattan’s southern tip, but a mental state of passage as well, a sense of the sublime, we humans so small, in contrast to nature’s massive forceful river and so small in contrast to the built structures of our own creation. With other areas of life needing attention, I took a hiatus from long distance open water swimming a few years ago. But, I’ve continued to swim several days a week, and particularly enjoy the public outdoor pool at John Jay Park on East 77th Street, one of the perks of summer in the city. And, I have signed up for the CIBBOWS (Coney Island Brighton Beach Open Water Swimming). Triple Dip, 1-2-or 3 mile swims, on September 15. CIBBOWS also offers a number of local open water open water swim gatherings and events, including open water swim clinics, and is well worth checking out. Looking for a nature connection to New York City through its waters? CIBBOWS awaits, as do the beaches at Coney Island, Rockaway, and Pelham Bay (and maybe one day, Manhattan).  On a friend’s recommendation, I am reading Circe, by Madeline Miller. Miller brings Greek and Latin myths to life, "novelizing" the stories of Homer, Aeschylus, Ovid, and Virgil. She creates an extended narrative that brings to light stories’ coherence with one another and animates the characters’ inner lives. Circe, the daughter of the sun god Helios and Perse, an Oceanid nymph, was a sorceress, whose magic derives in part from her understanding of the power of herbs and plants. On several occasions, she makes use of a flower, “pharmaka”, which turns creatures into their true selves. Administered to the poor, mortal fisherman, Glaucus, he becomes a sea God who rescues sailors from storms. Added to the bathing area favored by the beautiful yet conniving nymph Scylla, she turns into a tentacle sea monster, much like a giant squid. And through the use of plants, Circe turns Odysseus's ravenous and disrespectful sailors into pigs. Reading of Circe’s awareness of plants and their potency, their magic, underscores how nature can awaken our true selves. This isn't to suggest that our true selves are gods or raging demons. But time in nature aids the work of our parasympathetic nerves to help us relax and overcome the fight or flight reaction of sympathetic nerves, which read modern-day stimuli as threats. Nature has a way of releasing deeper truths, exhuming our inner state of being, one that can respond to nature's gifts, our home for 99.99% of the time humans and humanoid creatures have existed on our planet. Think about what true aspects of yourself a connection with nature might reveal. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed