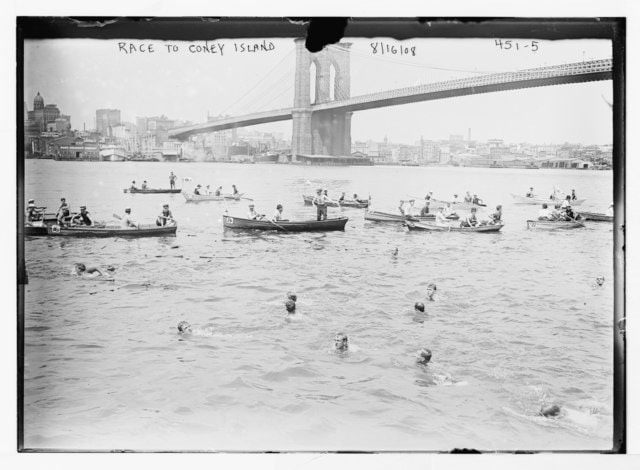

Bain News Service, publisher, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Bain News Service, publisher, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Hudson River, East River, Harlem River--Manhattan, as you know, is an island. But how often do we notice the waterways surrounding it and consider not only their presence, but the ebb and flow of their currents, their temperatures and micro-temperatures, and the ways they intersect? The density of Manhattan--with block after block of sky scrapers often blocking the horizon from view--contributes to waterway blindness, as does the legacy of Robert Moses’ city planning, which privileged cars over pedestrians by locating highways along the scenic margins of Manhattan. Many of us can go entire days, including commuting to and from Manhattan, without even seeing a waterway. Open water swimming offers a way to sense directly the powerful and magnificent waters surrounding our city, waterways created millennia ago that define Manhattan's island structure yet stand in sharp contrast to its built environment. Recently, a number of news articles have brought attention to Manhattan open water swimming, including articles about Ira Gershenhorn, Hudson River swimmer and clean water advocate; Jaimie Monahan, a New Yorker and champion open water, ice, and winter swimmer who aims to set a record as the fastest person to compete six marathon swims on six continents within 16 day; and the potential for creating a swimable beach on Manhattan as a way to escape the summer heat. Over the years, I have swum (not very fast) in a number of local open water events, including two four-person relays around Manhattan, several 6K “Little Red Lighthouse” swims in the Hudson, several swims around nearby smaller islands (Governors’ Island and Liberty Island), a 4-miler across the Long Island Sound, and a 3-miler across the Hudson at the Tappan Zee Bridge. This was in addition to out of town events, including 10 and 6 mile swims on Lake Memphremagog on the Vermont-Canada border, and crewing for various swims, including for a remarkable 15 year old swimming the 17-miles from Sandy Hook, New Jersey to Manhattan’s Battery. The local swims connected me with New York City’s surrounding waters, and as a result I never look at the waters the same way. Driving or biking along the Hudson in Manhattan, I notice that it is at times calm, and at other times ferocious. I notice areas of flatness, and areas of turbulence. Driving on the FDR, or over the 59th Street Bridge, I notice the racing tidal force pushing the East River northward. Swimming in nearby waters has attuned me to the wildlife of the waters, environmental conditions, and the impact of weather on the waters. The Little Red Lighthouse swims in the Hudson—the lighthouse is below the George Washington Bridge, on the East Side of the Hudson and was a subject of a lovely children’s book—ran north-to-south or south-to-north, depending on the in-bound and out-bound tide (the Hudson, as noted in an earlier blog, is a tidal estuary, with saline effects reaching 150 miles north to Troy, New York). The wave motion of a south–to-north swim on a windy day was particularly memorable, with the northward pull of the tide intercepting the southward pull of the current. Mr. Powell, my high school physics teacher, could have drawn a beautiful graph of the resulting wave motion of these two forces. Swimming in it required modulating stroke and breathing to this dual pattern, not unlike dancing to a complex beat. The Manhattan Marathon swims offered an opportunity to distill the differences in Manhattan’s three waterways: the East River, with the mix of currents at Hell’s Gate, where catching the wrong current would send one to the Long Island Sound yet hugging the Manhattan shoreline would add significant distance (I am forever grateful to my accompanying kayak guide for skillfully navigating that water); the relative calm of the Harlem River, which felt like a lazy river in a rural setting; and the sublimity of the Hudson, broad and powerful, where swimming with the tide could result in a pace of 6 miles an hour—in other words, like flying in the water or embodying Michael Phelps. Swimming under the George Washington Bridge, with a view of the bridge’s underside and a sense of proportion of its giant supporting stanchions ignited a sense of awe for the breadth and force of the Hudson and the human ingenuity to build such a structure. The pull of the water, the sense of passage under the bridge, its bold static arch and sentinel-like stanchions a contrast to the movement within movement of the water in which I was immersed and sensing with my full body (no wetsuits), and the rhythm of my arms stroking, legs kicking, and torso, head and neck rotating for breath, awakened a sense passage. The passage was not only a geographical transition into the waters south of the bridge, the home stretch toward Manhattan’s southern tip, but a mental state of passage as well, a sense of the sublime, we humans so small, in contrast to nature’s massive forceful river and so small in contrast to the built structures of our own creation. With other areas of life needing attention, I took a hiatus from long distance open water swimming a few years ago. But, I’ve continued to swim several days a week, and particularly enjoy the public outdoor pool at John Jay Park on East 77th Street, one of the perks of summer in the city. And, I have signed up for the CIBBOWS (Coney Island Brighton Beach Open Water Swimming). Triple Dip, 1-2-or 3 mile swims, on September 15. CIBBOWS also offers a number of local open water open water swim gatherings and events, including open water swim clinics, and is well worth checking out. Looking for a nature connection to New York City through its waters? CIBBOWS awaits, as do the beaches at Coney Island, Rockaway, and Pelham Bay (and maybe one day, Manhattan).

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed