|

A viral pandemic is spreading across the globe. We are advised to wash our hands, avoid touching our faces, maintain social distancing, cough and sneeze into our elbows, and self-quarantine if not feeling well. An invisible force of nature has led to illness and death, schools closing, social gatherings cancelled, and a plunge in the stock market. And, it highlights how interconnected we are.

What began in Wuhan, China has arrived in every continent except Antarctica, and is spreading within countries. Just thinking about the vectors of contact, multiplied across people infected, is mind boggling. An individual in a Westchester suburb of New York City with no recent history of travel to a hot spot is diagnosed with the virus and its illness COVID-19. His communities go on high alert; his house of worship shuts down, his office shuts down, his family and various contacts are found to be diagnosed. The virus pops up in Nassau County, Long Island; in Queens, in New Jersey, in Connecticut, far away from the initial U.S. hot spots of Seattle and California. And so many of us move into a state of hyper-awareness. Is that occasional cough a Coronavirus cough? Do I dare take the subway? Is that person coughing over there going to make me and my family ill? Do I even need to worry since I am not among the more vulnerable sub-populations (although loved ones are)? All if this vigilance, on top of contributing to workplace awareness and response planning in my day job, is making me a little nutty. I find myself experiencing tightness in my chest, and wondering if it is a sign of the COVID-19 - or more likely my tendency to feel that way when I am experiencing stress (and a day hunched over a computer to track the latest developments for my organization doesn't help). So I went for a walk. And I am reminded that there is a beautiful world out there. In case you haven't noticed, with the clocks springing forward over the weekend, darkness arrives at close to 7:30. And we can all probably agree that 70 degree weather in New York City before mid-March is alarming and a likely indicator of an existential crisis far greater than Coronavirus. .... But it did feel nice to walk in Central Park amid the soothing, warm air, to feel the sunlight and to notice the earliest of blooms, the beginning flowerings of dogwoods, cherry trees, azaleas and forsythias. None of this takes away from concern about a highly contagious virus that is potential deadly, particularly for vulnerable populations. But a walk outside noticing the beauty of evening light and early spring blooms sure helped to relieve that tightness in my chest. ----- From Having it Out With Melancholy by Jane Kenyon What hurt me so terribly all my life until this moment? How I love the small, swiftly beating heart of the bird singing in the great maples; its bright, unequivocal eye.

0 Comments

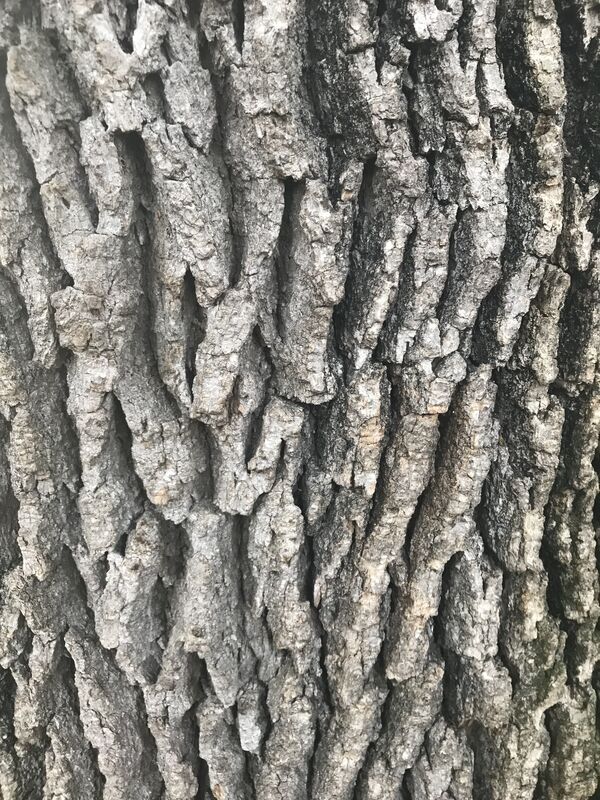

A coyote was recently sighted in Central Park, a reminder of how as cities and suburbs expand into wildlife habitats, wildlife increasingly ends up in our backyards, including urban parks. Somewhat surprisingly, urban environments--though posing unique threats to wildlife--can also be beneficial for wildlife, offering abundant food sources and even predictable ambient patters, such as morning and evening rush hour. Coyotes are not strangers to contemporary New York City. The Gotham Coyote Project, a group of researchers, educators, and students is working together to study the ecology of the northeastern coyote in New York City and the region. The project estimates that, as of 2018, 30-40 coyotes live in the New York City area, including in Queens near La Guardia Airport, the Bronx, Central Park, and Battery Park. Increasingly, as humans encroach on wildlife habitats, wildlife encroaches on human habitats. Books like Feral Cities and Zooburbia, describe ways that human and animal life overlap. Notes an article in The Guardian, "all around the world, city life seems to be increasingly conducive to wildlife. Urban nature is no longer unglamorous feral pigeons or urban foxes. Wolves have taken up residence in parts of suburban Germany as densely populated as Cambridge or Newcastle. The highest density of peregrine falcons anywhere in the world is New York; the second highest is London, and these spectacular birds of prey now breed in almost every major British city. And all kinds of wild deer are rampaging through London, while also taking up residence everywhere from Nara in Japan to the Twin Cities of the US." Coyotes in NYC remind us that the wild heart of life collides and coexists with us in our urban homes. Denuded of their leaves, the verdant raiments of Spring and Summer rendered brilliantly hued in Autumn, trees in Winter allow us to hone in on the subtle and not so subtle differences of their outermost layer, overlaying the wood and vascular cambium -- their bark. As you make your way about in Winter, take note of tree bark - its color, texture, and form. What colors do you see? Greenish gray? Silver or brown? Red undertones? Is it smooth--as is typically the case with young trees, much like smooth skin of young people--or deeply grooved and weathered, showing its years? Do its grooves appear as elongated parallel ridges or striations? Diamonds? Braided twists? Is the bark rigid? Flaky? Layered? Deep or relatively flat? How does it feel to the touch? Hard or soft? Every species of trees has its signature bark, and people knowledgeable about trees can identify them by their bark alone. Take advantage of the starker Winter landscape to appreciate the varied beauty of tree bark. I prefer winter and fall, when you feel the bone structure of the landscape. Something waits beneath it; the whole story doesn't show. -- Andrew Wyeth  Martin Luther King Day offers a time to reflect on the impact of the great civil rights leader and his legacy of respect. A corollary to respecting other human beings, regardless of race, ethnicity, or skin color is respect for nature -- respect for other leaving creatures and the ecosystems that support them. Respect for nature, like Civil Rights, is rooted in the notion of "inherent worth." In the context of environmental ethics, Paul W. Taylor, in his groundbreaking book Respect for Nature: A Theory of Environmental Ethics, describes "inherent worth" in this way: Our duties toward the Earth's non-human forms of life are grounded on their status as entities possessing inherent worth. They have a kind of value that belongs to them by their very nature, and it is this value that makes it wrong to treat them as if they existed as mere means to human ends. It is for their sake that their good should be promoted or protected. Just as humans should be treated with respect, so should they. (p. 13) There are a range of ways to regard nature, many of which ultimately are about what nature can do for people. Nature can be regarded as a resource to be exploited (e.g., "natural resources"), focused on energy, agriculture, timber, and extraction-oriented activities. It can be experienced as a playground for outdoor activities. Perhaps more nobly, nature can be considered a refuge, an escape from hectic modern life. It can be engaged with aesthetic appreciation and with scientific curiosity. Yet, all of these, notes Taylor, differ from the attitude of respect for nature grounded in a moral sense of nature's inherent worth. A sense of nature's inherent worth is central to a biocentric outlook on nature and the attitude of respect for nature. From the perspective of a biocentric outlook, writes Taylor, [O]ne sees one's membership in the Earth's Community of Life as providing a common bond with all the different species of animals and plants that have evolved over the ages. One becomes aware that, like all other living things on our planet, one's very existence depends on the fundamental soundness and integrity of the biological system of nature. When one looks at this domain of life in its totality, one sees it to be a complex and unified web of interdependent parts." (p. 44) Environmental ethics is not an obvious legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Civil Rights work. Yet, there are interrelated threads, rooted in the notion of inherent worth and an awareness of the inter-dependencies of living creatures. As King himself said, It really boils down to this: that all life is interrelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one destiny, affects all indirectly. On MLK Day, we can reflect on the wisdom and courage of the great Civil Rights leader, and the broad impact and application of his vision.  (c) Riley E. Carlson (c) Riley E. Carlson Time outside in Winter offers its rewards--pristine settings, a feeling of adventure, and the beauty of nature's muted palette. But let's face it. Winter tends to be a time of huddling indoors and enjoying warmth and shelter. In this way, we are no different than our fellow animals, and as with the shelters of other animals, our shelters make use of available natural features and materials. Consider caves and simple built structures, such as earthen pits covered with thatched roofs and tents. Writes Roma Agrawal in her delightfully informative and readable book Built: The Hidden Stories Behind our Structures, For a long time ... humans simply built from the materials that Nature provided, without changing their fundamental properties. Our ancient ancestors' dwellings were made from whatever they could find in their immediate surroundings: materials that were readily available and could be easily assembled into different shapes. With a few simple tools, trees could be felled and logs joined to create walls, and animal skins could be tied together and suspended to form tents. Nowadays, amid canyons of concrete, steel, and glass skyscrapers, it may feel like a stretch to imagine these simple structures occupying the land that is now New York City. But these were the structures used by the indigenous Lenape people and by European settlers, and many of the engineering principles of these structures find expressions in the giant skyscrapers that give Manhattan its signature skyline.  It's a new year and a new decade, a time for new beginnings and, with a nod to the number of the year we've entered, perhaps clearer vision of what we hope the coming time will bring. While we often think of Spring, with its plant life bursting forth, as a time of awakenings, Winter's shorter daylight hours and colder temperatures offers a time to retrench, restore, and rejuvenate, to collect one's energies and dive deeply into one's inner creativity. Indeed, writes the Italian poet Pietro Aretino, "Let us love winter, for it is the spring of genius." One also is reminded of T.S. Eliot's lines from The Wasteland: Winter kept us warm, covering Earth in forgetful snow, feeding A little life with dried tubers. While nature, with its withered stalks, may appear dormant in winter, there is a drawing inward that supports life and growth. Writes Gary Zukov, The winter solstice has always been special to me as a barren darkness that gives birth to a verdant future beyond imagination, a time of pain and withdrawal that produces something joyfully inconceivable, like a monarch butterfly masterfully extracting itself from the confines of its cocoon, bursting forth into unexpected glory. Allow yourself time during these wintry days to draw within, nurture, and replenish. Christmas season has arrived, and with it decorated trees and wreaths, harkening back to earlier, pagan traditions. In Landscape and Memory, Simon Schama describes these traditions in the context of a "verdant cross", a blending of tree symbolism and Christianity with ancient origins. Writes Schama,

"Tree cults were everywhere in barbarian Europe, from Celtic shores of the Atlantic in Ireland and Brittany, and Nordic Scandinavia, all the way through to the Balkans in the southeast and Lithuania on the Baltic.... Why should Christianity have denied itself the irresistible analogy between the vegetable cycle and the theology of sacrifice and immortality? Had it been adamantly ascetic, Christianity would have been unique among the religions of the world in its rejection of arboreal symbolism. For there was no other cult in which holy trees did not function as symbols of renewal. Even a summary list would include the Persian Haoma, whose sap conferred eternal life; the Chinese hundred-thousand-cubit Tree of Life, the Kien-mou, growing on the slopes of the terrestrial paradise of Kuen-Luen; the Buddhist Tree of Wisdom, from whose four boughs the great rivers of life flow; the Muslim Lote tree, which marks the boundary between human understanding and the realm of divine mystery; the great Nordic ash tree Yggdrasil, which fastens the earth between underworld and heaven with its roots and trunk; Canaanite trees sacred to Astarte/Ashterah; the Greek oaks sacred to Zeus, the laurel to Apollo, the myrtle to Aphrodite, the olive to Athena, the fig tree beneath which Romulus and Remus were suckled by the she-world, and of course... [the] fatal grove of Nemi, sacred to Diana, where the guardian priest padded nervously about the trees , awaiting the slayer from the darkness who would succeed him in an endless cycle of death and renewal" Noting how Christianity followed in this tradition he states, "It was to be expected, then, that Christian theology, notwithstanding its official nervousness about pagan tree cults, would, in the end, go beyond the barely baptized Yggdrasil of a twelfth-century Flemish illumination where the boughs of the world-tree support paradise. But it was only when the scriptural and apocryphal traditions of the Tree of Life were grafted onto the cult of the Cross that a genuinely independent Christian vegetable theology came into being." (219). Indeed, writes Schama, consider "the timber history of Christ": "born in a wooden stable, mother married to a carpenter, crowned with thorns and crucified on the Cross." Even lore around Christmas mistletoe has ancient tree cult origins. Schama notes that "according to Pliny, the druids believed mistletoe to grow in precisely those places where lightning, dispatched by the gods, had struck the [pagan] oak [of Jupiter]." As many celebrate the Christmas holiday with verdant symbolism, think about humans' long tradition of venerating trees.  With the first snow storm of the season hitting New York City, out comes the salt, sprinkled on sidewalks and streets to reduce ice formation and slippery surfaces by lowering the freezing point of water. The salt, formed eons ago in the ocean, with chlorine derived from volcanoes at the bottom of the ocean combining with sodium washed off the continents, to form sodium chloride. Salt deposits are left behind by oceans that have dried up, and much of the salt spread on roads in the New York City area is shipped from deposits in the Atacama Desert in Chile. The volume of salt distributed on roads and sidewalks is staggering: 55 billion pounds are distributed on U.S. roads every year. It can be detected miles from where it is deposited, sixty floors above the city streets, and runs off into nearby waters, increasing their salinity. And it impacts living organisms. Chemically similar to potassium, salt it can work its way into the potassium-supported functions within cells. However, it cannot perform the processes powered by sodium, and thus is harmful to many organisms. Yet, as described by Menno Schilthuizen in Darwin Comes to Town, some living creatures have evolved in urban areas--that is, have genetically mutated--in ways that enable them to survive the road salt inundation of sodium. "Organisms that manage to cope with saline situations have usually evolved mechanisms to counteract the salty onslaught on their cells. [Thus, ...] salt-tolerant beach plants colonize the hard shoulders of major inland roads, pushing out the regular verge verdure. But chances are that the animals and plants that are already there also evolve salt tolerance thanks to road salting." Schilthuizen describes a lab experiment in which batches of small crustaceans--water fleas--were placed in tanks with different salt concentrations to live for 10 weeks (5-10 generations). The descendants were then removed from their salty environments, cultured for 3 additional generations in tanks of unsalted freshwater, and then tested for their salt tolerance. It turned out that "the water fleas retained the evolutionary signature of having adapted to salt water. When placed in brackish water...the strains that had lived under moderate salt concentrations ...survived well, whereas the ones previously naive to salinity experienced only 46 percent survival." Humans are transforming the environmental conditions of the places we inhabit; while harmful to many creatures, some creatures evolve to survive the harsh conditions we create.  In my previous blog I described Naomi Sach’s and Gwenn Fried’s presentations and Regina Ginyard's and Jenn Hertzell's audience participation activity at The Transformative Properties of Horticulture symposium held on November 15. Concluding the activity was a presentation by Amos Clifford, founder of the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy Guides and Services, the organization from which I received my training as a forest therapy guide. It seems only appropriate to be writing about Amos’s presentation during Thanksgiving week, as there is so much about his insights to be thankful for, and in what is a virtuous circle, I am confident that he in turn would express his gratitude for more-than-human world around us. Amos began by asking if Forest Therapy can play a role in responding to the global climate crisis, or as he noted, what should more aptly be called simply “the crisis” given its broad scope: the omnipresence of plastics, the “insect apocalypse” and collapse of entire ecosystems. He noted that we are in a “liminal time” –- an in-between time when things are not predictable. This was his motivation in founding ANFT. In the course of a vision fast, he asked, “what can I do as I enter my elder year to help?” “We have to remember who we are in the context of this beautiful planet and all the beautiful creatures on this planet. We need to remember that we’re in relationship with more than human beings. This is not about being a naturalist or scientist. It is about being in our bodies. It is about being in our senses. It is about being here, not getting to there. … Plants are fundamental in what we do. Our relationship with plants, thinking of them as sentient beings, capable of having a relationship with us, thinking of the forest as sentient and intelligent. Science is beginning to catch up to this understanding.” Amos highlighted the importance of imagination, noting that Albert Einstein said that “imagination is more important than knowledge.” He encouraged the audience to think of imagination as a sensory field, one that inspires. "Through an imaginal journey we can explore trees, stones, clouds, and bird by shifting how we experience them. We can shift to a remembering, recognizing that it was not very long ago in human history that we thought of the more-than-human world as sentient." "People are born out of the Earth. We are a part of Earth. Earth has seeded within us the potential to transition into a deeper state of knowing. And now is when we need action. When do you write the best poetry in your life? The best songs? When you are suffering. May this be the time that the poetry of who we are can be beautiful." "We need to transition our way of thinking, to move away from desiring “more of” to rather something “different from”. We need a connection to nature that embraces whimsy, curiosity, and following nature’s simple pleasures. These are new ways of knowing and being, and they help we redefine “wellness” to take into account “what it means to be whole. We can't be whole apart from a relationship with nature, because we are nature." Amos asked audience members to take a look at their hands, and to appreciate all that they have done. He added, "The mind is wise enough to hold its place in the family of things. He conveyed the notion of "plants as persons" and noted how "plant blindness" has become a disease. "We overlook plants, misunderstand their time scale. For example, forests are migrating. Yet, they move in "forest time", over periods of time that are difficult for human beings to readily discern." Amos went on to postulate the notion of new ways of being and knowing in relationship with nature. He described the idea of "Earth Dreaming", which came to him in connection with the concept of an "entangled mind" and that "leads to the question of whether immersion in this field of vegetal learning cause an evolutionary leap, the Earth's invitation to learn a new way of being. Relationships are like neurons within an expanded mind. Think of the forest or plants and places as part of our brain. What is diversity and reciprocity? What if the entangled mind is what knows how to live?" How lucky we are to hear Amos's insights and perspective.  Last week I was fortunate to attend and offer a small Forest Therapy walk following a symposium on The Transformative Properties of Horticulture, sponsored by the Madison Square Park Conservancy. The symposium featured inspiring speakers engaged in breathtakingly impactful work. Naomi Sachs, a professor of therapeutic landscape architecture at University of Maryland and founder of the Therapeutic Landscapes Network, a resource for gardens and landscapes that promote health and well-being, spoke about "restorative landscapes" and the importance of providing access to nature in healthcare settings. Hospitals are stressful places where patients and their visitors are at their most vulnerable. “Health”, she added, is not just “not being sick”. It is also about physical, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing, which is enhanced by natural environments. She described the notion of “restorative landscapes”, which are landscapes that promote health and wellbeing, and could be as simple as a fire escape or memorial--any place that where a person can find peace and solace. Sachs described the many scientific and medical studies supporting the beneficial impact of nature, including—among medical patients—more rapid recovery from surgery, reduced patient complaints, and reduced need for medication, and--among the general population--improved memory and attention and a reduction in ruminative thoughts. Gwenn Fried, Manager of Horticulture Therapy Services at NYU Langone Medical Center, then spoke about therapeutic horticulture in public spaces and underscored the value of targeting the certain populations that can most benefit from it, including:

Regina Ginyard and Jenn Hertzell then engaged the audience in a networking activity focused on green spaces that give people joy. Ginyard is a founding member of Black Urban Growers (BUGS), an organization committed to "building networks and community support for growers in both urban and rural settings." Jenn Hertzell is a Bronx-based farmer and founder of At the Rood: An Herbal Eastery, Farm, and Apothecary that exists to create opportunities for people of the African Diaspora to hear their relationships with their bodies and with the earth. How fortunate we are that scholars and practitioners like Sachs, Fried, Ginyard, and Hertzell are improving lives through the transformative properties of horticulture. Stay tuned for my next blog entry to learn about what Amos Clifford said at the conference. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed