|

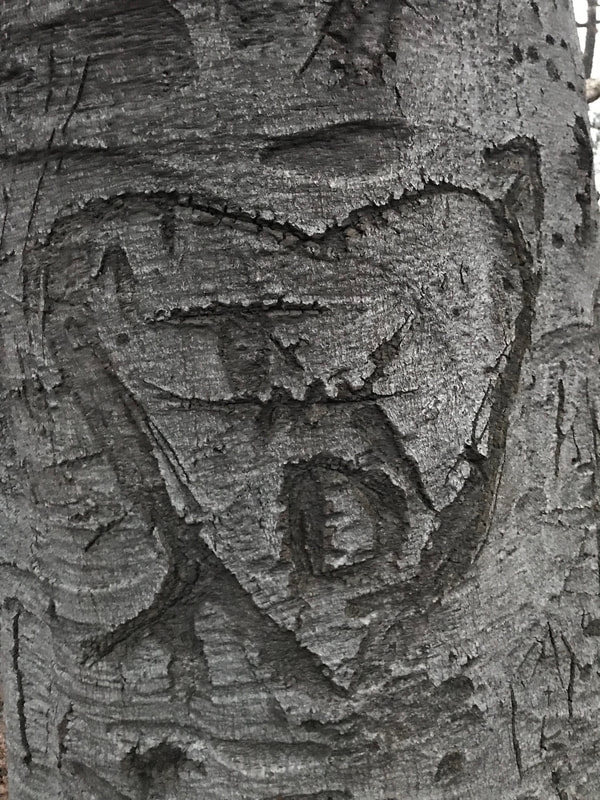

Trees invite expression of love, especially beech trees. With their smooth gray bark, it's difficult to find an older beech tree that does not have a heart with initials carved into its trunk--at least in Central Park.

Much as hearts are among the more popular tattoos inked onto human skin, the tendency to etch hearts onto the elephant hide-like bark of beech trees suggests that memorializing love comes from a place deep within us. There is something that impels us to mark our feelings of love in ways that pierce below the surface, perhaps because love itself is so deeply felt. Above are samples of hearts carved on beech trees in Central Park (alas, such etching harms the tree, inviting disease and if deep, disrupting the flow of nutrients). Did the love last? Did the lovers grow old together like the tree that display their affection? We will never know. But the expression of love lives on, preserved for decades on the bark of trees.

0 Comments

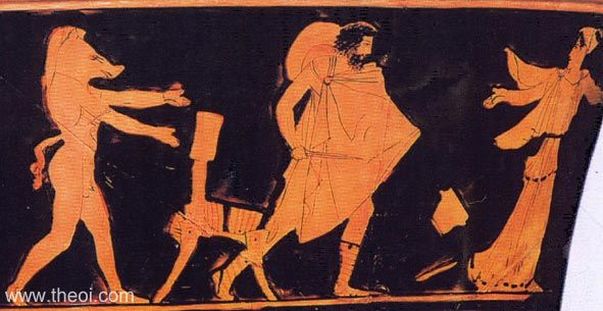

Luminescent, intricate photographic renderings of botanical forms -- "British Algae", otherwise known as seaweed -- appear in light blue and white against a darker blue background. This is the work of Anna Atkins, a long-obscured 19th Century botanist, artist, and pioneer in the application of photography to science. Atkins's work is on display through February 17 at the New York Public Library, Atkins applied the process of cyanotype, a cameraless photographic method utilizing light-sensitive paper to create in 1843 the first book illustrated exclusively with photographs. She donated the book, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, the Royal Society and dedicated it to her father, John Children, a fellow at the Royal Society. Children was friends with John Herschel, an astronomer and early photographic pioneer, who invented cyanotype in 1842 and introduced Atkins to the photographic medium. Atkins's application of photography to capture botanical images was a leap forward for scientific advancement. As noted in the NYPL exhibit: "In Renaissance Europe, artists' renditions exploded in popularity as the need arose for repeatable visual information to complement the printed word. The marked rise in the level of scientific inquiry from the 17th century forward paralleled a growing sophistication n these drawings and improved methods of distributing them. Among the most socially useful applications of art and science was the herbal, a genre of reference book on plants that describes their appearance as well as their medicinal, culinary or toxic properties. The hand of the artist, however, was not always in sync with the eye of the scientist, Rare was the individual who could reconcile the two. Difficulty emerged when the artist could not comprehend- or perhaps wasn't sympathetic to--the kind of information of greatest value to the botanist. Before British Algae, the only pictorial catalogues of botanical collections were illustrations with hand-rendered artists' impressions, or sometimes with actual dried plants affixed to their pages." The NYPL exhibit, the first dedicated to a full representation of Atkins's productions, not only offers insights into the history of photography and its application to science by a daring and innovative female scientist of the Victorian era, when gender roles usually relegated women to the domestic sphere. It also depicts flora in stunning detail and in ways that highly their exquisite beauty and symmetry. If cold weather is giving you the blues, step inside the NYPL to discover nature's blue prints.  One of the blessings of winter is the opportunity to observe the architecture of hardwood trees. Shorn of concealing leaves, their framework becomes visible -- fractal geometry, with branches splitting off and again dividing and splitting, from the thick central trunk, a torso of sorts, culminating in finer twigs, like small fingers, reaching outward and upward. Each type of tree displays unique morphology and growth patterns, with limbs branching off at wider or narrower angles, sometimes looping downward in a "u" shape before ascending, some knobby, gnarled and twisted, others soaring, erect, and tapering, some with great symmetry, others more variable -- a range of templates for achieving growth and access to nourishing sunlight. The texture of trees' bark becomes more apparent in the crisp light of winter, the furrowed, patterned grooves of elms appear in greater relief, the smooth, silvery surface of beeches almost shines, and one senses the tactile feel of the scaly, thinly-plated bark of London Plane trees. Knots, burls, fissures, and cavities become visible. And amid the the muted winter palette, one can discern bark's varying colors, ranges of browns, grays, white, and green, sometimes with tinges of orange or red, colors often overshadowed by inviting greens and flamboyant autumn shades in the year's other seasons. And then there is the experience of striding past a stand of denuded trees, their trunks tall and aligned, like sentinels. With each step, a movement felt more keenly horizontal in relation to the trees' verticality, one's perspective changes and the trees relative alignment with one another alters, with cinemographic and near-kaleidoscopic effect. Perhaps winter hardwoods offer a metaphor as we embark on a new year: unadorned, the trees exhibit their underlying stark beauty, strength and symmetry. All is apparent, nothing is concealed. Yet, even in this state, small buds are visible, waiting for the right conditions to bloom and flourish. "I prefer winter and fall, when you feel the bone structure of the landscape. Something waits beneath it; the whole story doesn't show." -- Andrew Wyeth  First Rockefeller Center Christmas tree, 1931 First Rockefeller Center Christmas tree, 1931 Few trees are more celebrated than the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree, a tradition that goes back to 1931, when workers building the area’s structures during the Great Depression pooled funds to buy a 20-foot balsam fir and decorated it with homemade garlands. The first public lighting, of a 50-foot tree, was in 1933, when Rockefeller Center made the tree an annual tradition. Over the years, the tree’s decoration has taken on various themes and reflected the issues of the times. As described by Dana Schultz: “During WWII, the tree’s décor switched to a more patriotic theme, with red, white, and blue globes and painted wooden stars. In 1942, no materials needed for the war could be used on the tree, and instead of one giant tree, there were three smaller ones, each decorated in one of the flag’s three colors…. Following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree was once again adorned in patriotic red, white and blue.” The 2018 Rockefeller Center Christmas, a 72 foot tall Norway Spruce, was sourced from Wallkill, New York, 75 miles north of Manhattan. Following the holiday, the tree’s lumber will be donated to Habitat for Humanity for home building, a practice since 2007. A media sensation surrounded by gawking crowds and adorned in 50,000 LED lights and a Swarovski crystal star weighing 900 pounds, the 2018 Rockefeller Center tree has come a long way from its more humble origins. Yet, it is a reminder of how every tree is a star in its own way, and how it's in our nature to be awed by trees.  Shantanu Kuveskar, CC BY-SA 4.0 Shantanu Kuveskar, CC BY-SA 4.0 Each season offers its gifts to our senses, and with autumn our senses awaken to the powerful changes in nature around us. We observe the leaves changing color and falling to the ground, we hear crisp leaves underfoot, we feel a stronger breeze and cooler temperature, and deep within our bodies, with the waning daylight, perhaps comes a gnawing desire to retreat to our homes a little earlier and stay snug and warm, much like fellow creatures that hibernate. Our sense us smell awakens too to the change in seasons. What causes that rich “autumn smell”? In a recent article journalist Matthew Cappucci provides insights: Leaves are designed to produce “food” for the plant — glucose — through the process of photosynthesis. They take in six carbon dioxide and six water molecules at a time and, with a bit of sunlight, reshuffle them to form glucose and six oxygen molecules. That’s why plants are said to “purify” the air. They add breathable oxygen to it. But even though this reaction produces energy for the plant, it takes a lot of work to sustain. In the fall, when the energy needed to create the “food” outweighs the energy afforded to the plant by the food itself, the leaves are no longer needed — and with that, the tree bids them farewell. When the leaves fall, they die. As they take their last breath, they “exhale” all sorts of gases through tiny holes known as stomata. Among these compounds released are terpene and isoprenoids, common ingredients in the oils that coat plants. Terpenes are hydrocarbons, meaning their main ingredients are hydrogen and carbon. Pinene, a species of terpene, smells like — you guessed it — pine. It’s a main ingredient to the saplike resin that repairs the bark of conifers and pine trees. Occasionally, these gas molecules excreted by plants — known as volatile organic compounds — interact with variants of nitrous oxide. This can lead to ozone production, which can smell a bit like chlorine or the exhaust of a dryer vent. In addition to the release of gases contained within dying vegetation, two other effects contribute to the emotion-evoking scent that accompanies a northwest autumn breeze: decomposing plant matter, and pollutants trapped at the ground levels during the fall months. The soil in most parts of the world is rich in Geotrichum candidum, a fungus that causes rotting and decomposition of fruits and vegetables and dense plant matter. In fact, Geotrichum candidum has been sampled on all seven continents. This is just one of many species that erodes away as deceased organisms, the chemical reactions of which contribute to the smell of “fall.” Allow your senses to connect with autumn.  Photo by Autumn Mott Rodeheaver on Unsplash Photo by Autumn Mott Rodeheaver on Unsplash We are deep into autumn, with a chill in the air and the hours of daylight diminishing, prompting leaves to change color and fall to the ground. What actually causes leaves to fall? In Lab Girl, Hope Jahren provides a beautiful description of the science behind falling leaves: If you rake fallen leaves into a pile and then examine them, you will see that each one shows a consummately clean break at the same place near the base of the stem. The fall of leaves is highly choreographed. First the green pigments are pulled back behind the narrow row of cells marking the border between stem and branch. Then, on the mysteriously appointed day, this row of cells is dehydrated and becomes weak and brittle. The weight of the leaves is now sufficient to bend and snap it from the branch. It takes a tree only a week to discard its entire year's work, cast off like a dress barely worn but too unfashionable for further use. Can you imagine throwing away all of your possessions once a year because you are secure in your expectation that you will be able to replace them in a matter of weeks? (p. 95) Autumn's falling leaves offers an opportunity to consider what we can discard. What is it that we no longer need? What is that we don't need now, but are confident we can restore in the future? In what ways are we comfortable or not about letting go?  Photo by Chris Lawton on Unsplash Photo by Chris Lawton on Unsplash Autumn is here, a time when nature calls out, demanding our attention as trees turn vibrant colors. There’s still much greenery in New York City, with trees showing only the slightest autumnal hues as of yet—greens a little faded, and a few yellow leaves emerging here and there. But every day brings perceptible changes, and this time of year offers a reminder of how the only constant is change. Trees slowly change colors, new migrating birds enjoy a stopover during their travels south, nighttime arrives a little earlier each day, and the air becomes cooler. And so too, we change a little every day. As Thoreau noted, “the seasons and all their changes are in me”. Over the next few weeks the trees will exhibit spectacular colors and then will be bare, their leaves having fallen to the ground. This time of year is rich in metaphor, perhaps a sense of the passing of one’s prime and a hint of mortality: That time of year thou mayst in me behold When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, Bare ruin'd choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. --From Sonnet 73 by William Shakespeare But need that really be our perspective? What we know is that nature exists in cycles, as do we. From autumn and winter come spring and summer, new life emerging in continual cycles of birth, life, death, and regeneration. There will be new springs and new summers, and with this time of heightened awareness of change comes awareness of potential and expectations, of new opportunities, with each season offering its gifts.  On a friend’s recommendation, I am reading Circe, by Madeline Miller. Miller brings Greek and Latin myths to life, "novelizing" the stories of Homer, Aeschylus, Ovid, and Virgil. She creates an extended narrative that brings to light stories’ coherence with one another and animates the characters’ inner lives. Circe, the daughter of the sun god Helios and Perse, an Oceanid nymph, was a sorceress, whose magic derives in part from her understanding of the power of herbs and plants. On several occasions, she makes use of a flower, “pharmaka”, which turns creatures into their true selves. Administered to the poor, mortal fisherman, Glaucus, he becomes a sea God who rescues sailors from storms. Added to the bathing area favored by the beautiful yet conniving nymph Scylla, she turns into a tentacle sea monster, much like a giant squid. And through the use of plants, Circe turns Odysseus's ravenous and disrespectful sailors into pigs. Reading of Circe’s awareness of plants and their potency, their magic, underscores how nature can awaken our true selves. This isn't to suggest that our true selves are gods or raging demons. But time in nature aids the work of our parasympathetic nerves to help us relax and overcome the fight or flight reaction of sympathetic nerves, which read modern-day stimuli as threats. Nature has a way of releasing deeper truths, exhuming our inner state of being, one that can respond to nature's gifts, our home for 99.99% of the time humans and humanoid creatures have existed on our planet. Think about what true aspects of yourself a connection with nature might reveal.  Hangman's Elm, photo by Nancy Kopans Hangman's Elm, photo by Nancy Kopans With the United States commemorating its 242nd birthday comes an opportunity to consider creatures that were alive on July 4, 1776 and are still alive today: trees. New York City is fortunate to have several trees that were alive during this time. Manhattan’s oldest tree, estimated to be at least 315 years old, is an English Elm located in the northwest corner of Washington Square Park. Though named the “Hangman’s Elm” it has not witnessed any hangings. In 1827 Alfred Pell sold 2.5 acres of land that included the tree to help create the park. As English elms are not native to the U.S., the tree is thought to have come from seeds brought to the continent on a Dutch West India Company ship, and thus is an early immigrant that now stands sturdy and tall. The Hangman's Elm is not the only tree in Manhattan that was alive in 1776. George Washington is rumored to have watched the 1776 battle of Washington Heights from the shelter of an elm at 163rd Street and St. Nicholas Avenue, a tree named “the Dinosaur” that is over 300 years old. In an isolated part of Alley Pond Park in Bayside Queens, near the intersection of the Cross Island Parkway and the Long Island Expressway at 58th Road and East Hampton Boulevard sits “the Queens Giant,” a 134-foot tall tulip tree estimated to be 350 to 450 years old. And, a 145-foot talk tulip tree in Staten Island’s Clove Lakes Park is at least 300 years old. The Bronx and Brooklyn do not appear to have trees that were alive in 1776. However, they do have some very old trees. The oldest tree in the Bronx is thought to be an over-200 year old white oak located near the 18th hold of Pelham Bay park’s Split Rock Golf Course. The oldest tree in Brooklyn is likely to be among one of the 30,000 trees in Prospect Park’s vestige of the last remaining natural forest in Brooklyn. In 2009, a 220-year old black oak in Prospect Park was uprooted in a storm. With longevity that stretches the imagination, for the entirety of their lives these ancient living creatures have stood in the same place. Hangman's Elm, The Dinosaur, the Queens Giant, and Staten Island's tulip tree were alive during the times of the Dutch and British occupation, before the United States was a sovereign country. In 1776 the population of New York City (at least of those of European origin) was about 20,000 and plummeted to nearly half of this following the American Revolution, with the departure of the Tories. Inhabitants clustered at the tip of Manhattan. Canal Street was sparsely populated, and Greenwich Village and beyond were rural. The population would grow to 38,000 by 1790 and would multiply over time. And throughout this time stood the very same trees described above, witnesses to generations of immigrants--including my ancestors from Eastern Europe--crossing vast oceans, witnesses to streets paving over the land and to bridges and buildings rising; year after year and ring after ring, they have witnessed New York City transforming from a small overseas outpost into a world city. One wonders what stories the trees would tell if they could speak.  Running around the Central Park Reservoir this evening, I noticed the stunning cherry blossoms in full bloom. Like delicate pompoms in shades of white, pink, and deeper pink, the clusters of flowers with their smooth, silky small petals decorated the trees' contrasting dark, thick and cracked bark. A strong breeze burst across the scene. The cherry tree branches waved, and petals began to fall. Like snowflakes, each one of the hundreds in motion found its own way to the ground, in its own dance of drifting, twirling, fluttering, and spinning, a collective ballet of pearly pastel petals, like tiny ballerinas in pink slippers. Enchanted by the beauty, I also felt a tinge of melancholy. Time was passing. With each petal dropping the flowers were slowly fading. Beauty and death, hand in hand. ---- Blossoming cherry- gentle breeze wafted away a pink cloud --Marinko Kovačević Cherry blossoms the old woman’s appearance as a young girl --Dietmar Tauchner My heart too is floating through the air – cherry blossoms --Paul Smith |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed