Sun, moon, Hoboken, and the Hudson Sun, moon, Hoboken, and the Hudson Summer solstice, when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky, is an opportunity to connect with cyclical changes and embrace the bounty of nature around us. Summer is upon us, a time of abundant growth. The day that provides the most light, it is perhaps then a time for enhanced clarity and insight as well as chance to appreciate the world's plenitude. Derived from the Latin words "sol" (sun) and "sistere" (to make stand), the word "solstice" connotes an inflection point, a moment when what is before differs from what is after, as is fitting for the day that marks a shift from the sun progressing northward to tracking southward and with this a shift from lengthening daylight hours to shortening daylight hours. Humans have a rich traditions honoring the summer solstice. Ancient Northern and Central European pagans--including Germanic, Celtic and Slavic tribes--celebrated Midsummer with bonfires, which were thought to enhance the sun’s energy and promote a good harvest for the fall. Early Christians celebrated the day as St. John's Day, commemorating the birth of John the Baptist. The Great Pyramids of Egypt are situated such that, from the viewpoint of the Sphinx, the sun sets directly between two of the pyramids on the summer solstice. The ancient Chinese regarded the summer solstice as connected with the feminine force “yin,” and celebrated with festivities honoring Earth, femininity. The Mayans of Central America built structures to align with the sun's solstice path. And many Native American tribes engaged in solstice rituals, some of which continue to be practiced. The Sioux sun dance entails cutting and raising a tree as a symbolic connection between the heavens and Earth, placing teepees in a circle to represent the cosmos., and participants decorating their bodies in colors of red (sunset), blue (sky), yellow (lightning), white (light), and black (night). While many ancient cultures were attuned to the sun's cycles and engaged in solstice rituals, contemporary urban dwellers may fell less connected to this astronomical happening. But as entrenched as we may be in our day-to-day lives, the eternal dance between the Sun and Earth continues, a reminder of the extent of time beyond humanity and forces that are bigger than ourselves.

1 Comment

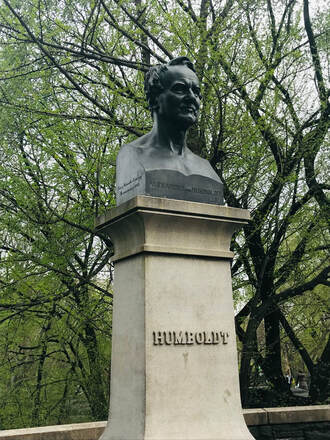

Botanists call flowers that have either male or female sex organs "imperfect", whereas flowers that contain both male and female sex organs are called "perfect". What a contrast to the negative views about human sexual diversity among all too many communities! June marks the arrival of "Pride Month", celebrating sexual diversity and gender variance. The month includes parades and other events to foster a positive, self-affirming stance against violence and discrimination toward LGBTQ people. June, 2019 promises to be the largest celebration of LGBTQ pride in history as it marks the 50th anniversary of the rebellion at NYC's Stonewall Inn in response to a police raid. Tolerance for human gender diversity may be an ongoing struggle, but gender variability is well recognized in the plant kingdom. Some trees, such as white ash and willow, have male and female flowers on different trees (that is, individual trees bear either male or female flowers). Others, such as beech and oak, have separate male and female flowers on the same tree. And others, such as magnolias, serviceberries, and elms, produce flowers with both male and female parts. That gender isn't binary is apparent in the plant kingdom. And, as the courageous people standing up for LGBTQ rights have shown us, gender isn't binary among humans either. Rather, among many natural creatures, ourselves included, there are variations of gender expression, with gender manifesting along a spectrum rather than black or white. There is much that plants can teach us, including that sexuality manifests in diverse ways.  I am a restless person. Left to my own when confronted with free time I like to go elsewhere, to get away and explore places near and far, other countries, other landscapes, other neighborhoods, and I am fortunate that circumstances allow me to do so. Restlessness has had its rewards. It has introduced me to different people and cultures, to new perspectives and has broadened my sense of natural and human history and activity. At the same time, it can take a lot of resources to be on the go, including time, money, and pollution-emitting carbon. Through hiking, exploring and guiding forest therapy walks, I spend much time in the presence of trees, pausing to take in their presence, to notice their form, and to contemplate their lives. Unlike animals, trees can't run away from their predators. They live their entire existence, sometimes hundreds of years, in one place (200 years in the life of a tree is the equivalent of 40 human years). Not able to run away or fight with tooth and claw, they carry their own medicine and systems to ward off danger. There's a reason so much of our medicine derives from plants: Imagine what trees have witnessed over the years as their trunks grow tall and thick and their branches reach skyward! Of course, trees are hardly still. From large vascular systems transmitting xylem and phloem to micro-activity on a cellular level, there is much movement, even if it isn't always visible to us. Yet, other than through the disbursal of seeds, trees are not mobile, whereas we are. As a human, I am animal, with muscles and limbs that enable me to ambulate and senses that enable me to to be drawn to what I need or to turn away from what is unpleasant or dangerous. This way of being is as central to me as it is to any other creature in the animal kingdom. Yet there is much that trees can teach us. Lately I've been thinking a lot about tuning in from time to time to a tree's perspective and the lessons to be learned. Without the impossible task of abandoning my animal self, maybe there is something to be said for staying more local, for standing tall while the activity of the world happens around me. What lessons would I absorb? What powerful medicine might I generate from such a stance? I recall the snarky word play, "Make like a tree and leave!" Cute, maybe, but what a brusque and inapt dismissal of our botanical, oxygen-providing neighbors on which we depend. Maybe it's time we "Make like a tree... and stay."  They stand tall, nurturing their offspring to enhance their chances of growing steadily and sturdily. They support their neighbors, transmitting messages across vast and intricate networks to ensure the community’s safety and well-being. They have withstood the cycles of many years, including challenging conditions, yet persist with grace and beauty. They are mothers – mother trees. Much attention has focused lately on the networked nature of forests. Trees exist not simply as individuals but within a highly collaborative, interconnected system, communicating through elaborate circuitry of fungi and root tips. "Forests", notes forester Peter Wohlleben in The Hidden Life of Trees, are superorganisms with interconnections much like ant colonies" Key to this interconnectedness are "Mother Trees", a notion pioneered by Scientist Suzanne Simardin (who appears as a fictionalized character in Richard Powers' The Overstory, the subject of the prior blog). The dominant trees in forests, Mother Trees function as central nodes for extensive underground networks of roots and mycorrhizal fungi. They nurture young trees by spreading fungi to them and conveying needed nutrients. Mother Trees also restrain the unfettered growth of young trees so that they can grow in ways that make them sturdier and more resilient.Writes Wohlleben: " Young trees are so keen on growing quickly that it would be no problem a all for them to grow about 18 inches taller per season. Unfortunately for them, their own mothers do not approve of rapid growth. They shade their offspring with their enormous crowns, and the crowns of all the mature trees close up to form a thick canopy over the forest floor. This canopy lets only 3 percent of available sunlight reach the ground and, therefore, their children's leaves. Three percent--that's practically nothing. With that amount of sunlight, a tree can photosynthesize just enough to keep its own body from dying. There's nothing left to fuel a decent drive upward or even a thicker trunk .... [S]low growth when the tree is young is a prerequisite if a tree is to live to a ripe old age. ... Thanks to slow growth, their inner woody cells are tiny and contain almost no air. That makes the tree flexible and resistant to breaking in storms." Slow growth also makes trees resistant to disease-bearing fungi,, which has difficulty penetrated the their tougher trunks. In the meanwhile, over a period that could last 200 years (the equivalent of 40 human years), the Mother Tree passes along sugar and other nutrients to the offspring. "You might even say they are nursing their babies," notes Wohlleben. Thanks to the attentiveness of Mother Trees, young trees can grow up strong and resilient, and forests can thrive. The same can be said for the roles of mothers (and fathers) within human families and communities. On this Mother’s Day, consider the Mother Trees around you.  New York is the epicenter of the book publishing industry. So, in exploring NYC nature connections it is apt to note the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for fiction awarded to Richard Powers' The Overstory, a novel in which trees shape the lives of nine characters and are so vividly evoked as to be characters too. In addition, Victoria Johnson's American Eden was a finalist for the Pulitzer for history. American Eden is a riveting biography of David Hosack, visionary physician and botanist during the early Republic who created the New York's first botanical garden (more about this terrific book in a later blog). Nature certainly received much attention from this year's Pulitzer Prize Board. The Pulitzer Prize Board describes The Overstory as "An ingeniously structured narrative that branches and canopies like the trees at the core of the story whose wonder and connectivity echo those of the humans living amongst them."....a sweeping, impassioned work of activism and resistance that is also a stunning evocation of—and paean to—the natural world. From the roots to the crown and back to the seeds, The Overstory unfolds in concentric rings of interlocking fables that range from antebellum New York to the late twentieth-century Timber Wars of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. There is a world alongside ours—vast, slow, interconnected, resourceful, magnificently inventive, and almost invisible to us. This is the story of a handful of people who learn how to see that world and who are drawn up into its unfolding catastrophe." With stirring, incisive descriptions, Powers awakens deep, limbic understanding of humans' biological and emotional connection to the natural world and the primacy of trees. “This is not our world with trees in it" he writes. "It's a world of trees, where humans have just arrived.” And what lessons there are to be learned from trees. Here's a passage I particularly like, one that portrays survival of the fittest not as fierce drama played out through competition among individuals but rather as a result of successfully networked, interrelated, and cooperative communities: "The things she catches Doug-firs doing, over the course of these years, fill her with joy. When the lateral roots of two Douglas-firs run into each other underground, they fuse. Through those self-grafted knots, the two trees join their vascular systems together and become one. Networked together underground by countless thousands of mile of living fungal threads, her trees feed and heal each other, keep their young and sick alive, pool their resources and metabolites into community chests.... Her trees are far more social than [she] suspected. There are no individuals. There aren't even separate species. Everything in the forest is the forest. Competition is not separable from endless flavors of cooperation. Trees fight no more than do the leaves on a single tree. It seems most of nature isn't red in tooth and claw, after all." There is much to learn from trees.  Alexander von Humboldt statue near Central Park Alexander von Humboldt statue near Central Park Inconspicuously situated at Central Park West and 77th Street stands a statue of Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), largely forgotten in the English-speaking world. As we approach Earth Day it is timely to consider the impact of this extraordinary polymath who invented the concept of nature's inter-connected forces and unity. At a time when Enlightenment philosophers were still grounded in Aristotle's view that "nature has made all things specifically for the sake of man" Humboldt saw the natural world as an interconnected, fragile web of life. Humboldt's textual works, Personal Narrative, Views of Nature, and Cosmos, as well as political essays about the colonies, and his maps and graphical depiction of climate zones, inspired scientists, leaders, poets, and thinkers including Johann von Goethe, Charles Darwin, Thomas Jefferson, Simon Bolivar, Jules Verne, William Wordsworth, early environmentalist George Perkins Marsh, Erst Haeckel who term Humboldt's discipline "ecology", Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. Entire philosophical and literary movements--German Idealism, Romanticism, and Transcendentalism--can trace their lineage to Humboldt and he revolutionized fields as wide ranging as agriculture, meteorology, zoology, geology, hydrology, and botany. Over 300 plant and 100 animal species are named after him, as are minerals, mountains, geologic formation, glaciers, waterfalls, bays, state and national parks, moon craters, and an asteroid--more than are named after anyone else. At the source of Humboldt's influence was his relentless energy and curiosity, which in the early 1800s led him to travel widely to places where few Europeans had traveled before to conduct hands-on scientific experiments, map geologic characteristics, and collect and record botanical samples. With collections of the latest instruments, ranging from telescopes and microscopes, to barometers and pendulum clocks and compasses, he traveled 1700 miles of Venezuela's Orinoco River to the Amazon River basin, across Cuba, Mexico and Peru, (where he climbed Mount Chimborazo, an inactive volcano of nearly 21,000 feet) and across the mountains of Kazakhstan. From evidence accumulated during his travels, he pieced together systemic patterns, similarities, and connections across contents, inventing the classification of plants by climate zones rather than taxonomy. Observing the coastal matching of Africa and South America, he sensed an ancient connection between the continents that presaged our understanding of plate tectonics. Humboldt also identified the devastating ecological consequences of deforestation, ruthless irrigation, and cash crop agriculture, decrying the impact on habitats of man's "insatiable avarice”. Moreover, Humboldt sensed and observed nature not only empirically but viscerally and emotionally. "Nature", he wrote to Goethe, "must be experience through feeling." In her thrilling and meticulously researched biography of Humboldt, The Invention of Nature, (2015), Andrea Wulf reminds us of the contributions of this influencer of influencers and restores his rightful place among the pantheon of scientists. With the arrival of Earth Day, consider the impact of Humboldt; there are few better ways to do so than through Wulf's magnificent biography.  Heightened attention to early flower blooms, described in my previous blog, has awakened my visual awareness and made me more attuned to forms and structures everywhere. Lately I've been particularly attuned to surfaces. By "surfaces" I mean the outermost layer, perceived by sight and touch--boundaries and edges that define, separate, and connect. Consider the many ways to describe surfaces, the characteristics that define them, to name a few: smooth, rough, patterned, textured, hard, soft, straight, curved, color, symmetrical, matte, shiny, reflective. And often, surfaces become all the more intricate the closer one looks. What appears as smooth may in fact be comprised of grooves and particles, with infinite complexity. City life offers an opportunity to notice the surfaces of our built environment, the geometric, smooth facades of buildings, sidewalks, stairways, and interior spaces--walls, floors, ceilings, furniture. What a contrast these views are to the undulating, uneven and surprising surfaces of the natural environment, of trees, flowers and shrubs growing along streets and in parks, of rocks and water. Some say that the "Euclidean geometry" of our built environment impairs our "visual fluency", that we innately crave the visual complexity offered by natural environments, visual fields that feed our brains' ability to absorb complexity. Yet, it is worth considering that the materials that create our built environment derive from natural materials: wood harvested, stones gathered and cut, and metals mined and smelted, transformed from their natural state to be put to our use. On a micro-level, their true natural forms become apparent: the cellular structure of wood, and crystalline structure of metals and rocks. What began as an ordinary day transformed into sensory adventure as I tuned into the surfaces around me.  As we honor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and reflect on the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 60s as well as issues of racial justice and equality that need attention today, we also have an opportunity to consider how the values underpinning civil rights apply not only among people -- across race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexual orientation, age, disability, and religion -- but also to our relationship with nature. Fundamental to civil rights is a moral attitude of respect, compassion, appreciation for one another's inherent, integral worth, and a sense of community, interconnectedness, and interdependence. The same ethos applied to our relationship with nature -- a perspective proffered by a number of writers, artists, poets, environmentalists and philosophers, and embedded in many religious practices and indigenous cultures -- would radically transform how we engage with the natural world. It would alter how we organize our business, social, and political conventions in connection with nature, from resource extraction, conservation, pollution management, and energy development, to how we choose to engage our leisure time, to how we design our homes and communities. And in turn, by altering tendencies to objectify inhabitants of the living world around, cultivating respect for nature likely would also enhance our respect for other humans. We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” ― Aldo Leopold  Witches Sabbath, Claude Gillot 1732 Witches Sabbath, Claude Gillot 1732 Witches, ghosts, and werewolves: fear-inducing outliers brewing powerful potions, apparitions defying the normal cycle of life and death, humans metamorphosing into savage canine creature. If one can step away from the commercial hype, Halloween reminds us of places and times where nature’s wilder manifestations were anthropomorphized. In Landscapes of Fear, Yi-Fu Tuan explores ways in which threatening aspects of nature—fears of drought, flood, famine, and disease shared by entire communities, and fears haunting the individual imagination—were given shape and tamed through myth, stories, and anthropomorphizing. Writes Tuan (pp. 105-112): "Dark nights curtail human vision. People lose their ability to manipulate the environment, and feel vulnerable. As daylight withdraws, so does their world. Nefarious powers take over…. People the world over have shown a tendency to anthropomorphize the forces of nature. …[T]he physical environment of dark nights … acquires an extra dimension of ominousness, beyond the threat of natural forces and spirits, when it is identified with human evil of a supernatural order, that of witches or ghosts." Witches defy social values. They dwell in untamed places outside standard human habitation—deep in forests or mountainous—and are closely associated with wild animals that defy human control: wild goats and horses (Europe); toads, snakes, lizards, frogs, jackals, leopards, bats, owls, and nighttime screeching monkeys (Uganda); hyenas and black cobras (Sudan); and dressed in skins of wolves and coyotes – werewolves (Navajo). They "are a force for total chaos, and they are closely associated with other forces or manifestations of chaos such as dark nights, wild animals, wild bush country, mountains, and stormy weather." Your costumed neighborhood trick-or-treaters might be a far cry from the bone-chilling renderings conceived by people trying to make sense of nature's more fear-inducing tendencies. But consider how cultures, living without electric lights and ease of communication across villages, coped with frightening aspects of nature. Maybe, for a moment, from the comfort of your built environment, and between sampling candy corn and observing various ninjas, princesses, and superheroes, you can sense how the supernatural helped explain the natural. Song of the Witches William Shakespeare, from Macbeth Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn and caldron bubble. Fillet of a fenny snake, In the caldron boil and bake; Eye of newt and toe of frog, Wool of bat and tongue of dog, Adder's fork and blind-worm's sting, Lizard's leg and howlet's wing, For a charm of powerful trouble, Like a hell-broth boil and bubble. Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn and caldron bubble. Cool it with a baboon's blood, Then the charm is firm and good.  Photo by Nancy Kopans Photo by Nancy Kopans September is here, a time of transitions. Children return to school and, with summer vacations now a pleasant memory, work tends to ramp up. With the days getting shorter many of us turn indoors earlier. We are nearing a time of harvest, and here and there we might notice a leaf’s changed color, a harbinger of the radiance of autumn to come. In the Jewish calendar, a lunar calendar, we are nearing the end of the month of Elul, the days that lead up to the New Year, Rosh Hashanah. Whether or not you are Jewish or religiously-minded, there is something apt about this time of year being the New Year, a time of reflection and a time of a long cycle of new beginnings. A parable teaches that in the month of Elul “God is in the field”. That is, God is not sequestered on the palace throne, surrounded by guards, but rather has ventured into the countryside to meet ordinary people and grant their requests. God is outside and accessible. This time of year thus asks that we be attuned to what is around us and to open our senses to an awareness of a divine presence in nature. It reminds us of the feeling of “what is bigger than ourselves” that we can experience when in nature. Others have noted the sense of the divine in nature. As Thoreau wrote, “Nature is full of genius, full of divinity. (Journal, January 5, 1856). He defined his “profession” as “to be always on the alert to find God in nature—to know his lurking places. To attend all the oratorios—the operas in nature.” (Journal, September 7, 1851). Consider the wisdom of opening one’s senses to the divine in nature, to attend its “oratorios” and “operas” and to be reminded of what is bigger than ourselves. |

About this Blog

Hi! I'm Nancy Kopans, founder of Urban Edge Forest Therapy. Join me on an adventure to discover creative ways to connect with nature in your daily life, ways that are inspired by urban surroundings that can reveal unexpected beauty, with the potential to ignite a sense of wonder. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed